It’s a common argument among climate deniers: scientific models cannot predict the future, so why should we trust them to tell us how the climate will change?

Muddling weather and climate

Deniers often confuse the climate with weather when arguing that models are inherently inaccurate. Weather refers to the short-term conditions in the atmosphere at any given time. The climate, meanwhile, is the weather of a region averaged over several decades.

Weather predictions have got much more accurate over the last 40 years, but the chaotic nature of weather means they become unreliable beyond a week or so. Modelling climate change is much easier however, as you are dealing with long-term averages. For example, we know the weather will be warmer in summer and colder in winter.

Here’s a helpful comparison. It is impossible to predict at what age any particular person will die, but we can say with a high degree of confidence what the average life expectancy of a person will be in a particular country. And we can say with 100% confidence that they will die. Just as we can say with absolute certainty that putting greenhouses gases in the atmosphere warms the planet.

Strength in numbers

There are a huge range of climate models, from those attempting to understand specific mechanisms such as the behaviour of clouds, to general circulation models (GCM) that are used to predict the future climate of our planet.

There are over 20 major international research centres where teams of some of the smartest people in the world have built and run these GCMs which contain millions of lines of code representing the very latest understanding of the climate system. These models are continually tested against historic and palaeoclimate data (this refers to climate data from well before direct measurements, like the last ice age), as well as individual climate events such as large volcanic eruptions to make sure they reconstruct the climate, which they do extremely well.

No single model should ever be considered complete as they represent a very complex global climate system. But having so many different models constructed and calibrated independently means that scientists can be confident when the models agree.

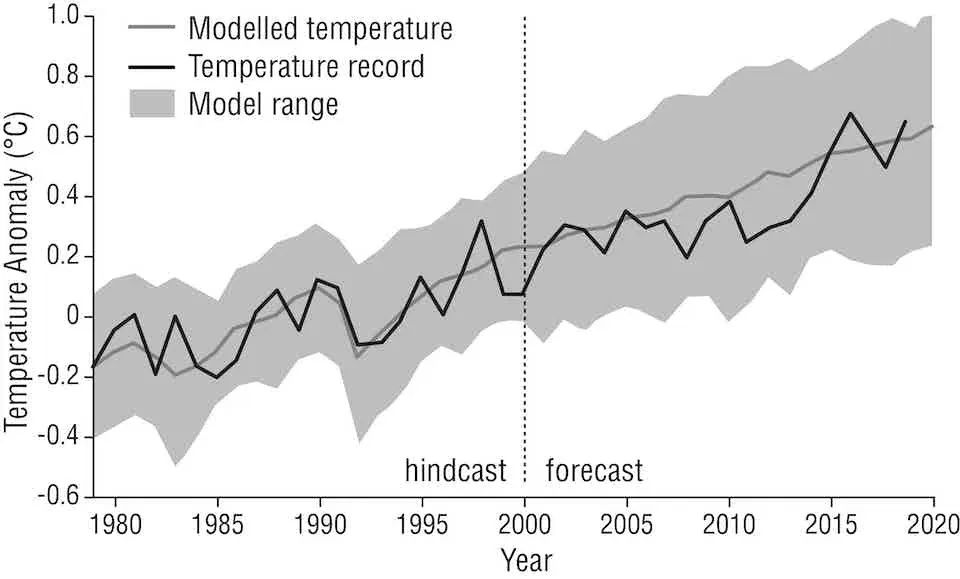

Model predictions from the 1970s and 1980s compare stunningly well with the warming trend that actually occurred over the last four decades. And scientists have been continually testing and improving these models ever since, meaning their predictions are a very robust outcome of our science.

Errors about error

Given the climate is such a complicated system, you might reasonably ask how scientists address potential sources of error, especially when modelling the climate over hundreds of years.

The biggest source of uncertainty in all climate change models is how much greenhouse gases humanity will emit over the next 80 years. Scientists account for this by working with economists and social scientists to build scenarios of the future with different emissions trajectories.

Scientists are very aware that models are simplifications of a complex world. But by having so many different models, built by different groups of experts, we can be more certain of the results they produce. All the models show the same thing: put greenhouses gases into the atmosphere and the world warms up. We represent the potential errors by showing the range of warming produced by all the models for each scenario.

In its sixth assessment of the science of climate change, published in August 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that “it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land”. How human activity will continue to affect the climate is a difficult question primarily because we do not know how the world will respond to this crisis. But we can count on models, which have a proven record of accuracy, to help us navigate what the future is likely to hold.

Source: Mark Maslin (UCL), The Conversation

From creating realistic virtual images and offering deep insights into writing copy and campaign ideas, the advertising industry is undergoing a significant transformation driven by generative artificial intelligence (AI).

It’s hardly surprising why.

According to Forbes, top-performing companies are more than twice as likely to be using AI for marketing.

Not only that, the AI-assisted digital ads business is expected to draw $192 billion (€175.6 billion) annually by 2032, according to Bloomberg Intelligence research.

McKinsey & Company, the global management consulting firm, says generative AI's impact on productivity could add trillions of dollars in value to the global economy - "and the era is just beginning".

Meanwhile, consultancy giant Accenture announced a €2.7 billion investment in AI, doubling its talent pool from 40,000 to 80,000.

With the technology continuing to gain traction, we are witnessing just the beginning of an era that holds tremendous promise for advertising.

Yet, as the industry quickly jumps to explore how AI can improve the overall performance and impact of advertising campaigns, Peter Huijboom, Global CEO of Dentsu - one of the world's largest marketing and advertising agency networks - says advertisers should look further, by analysing how to drive more sustainable practices and understand "what it will mean for the human being".

We’re at the stage where most advertisers are exploring the best applications for the technology, and evaluating how to make their processes more efficient, says Huijboom, "but if we move it one stage further, it will definitely have an effect on sustainability”.

Attention is the new sustainable currency

The advertising industry plays a crucial role in driving society towards a net-zero future, he tells Euronews Next at this year’s Cannes Lions Festival of Creativity, and the new currency is the "attention economy".

By prioritising attention, advertisers can determine which means of communication has the most impact, thus optimising resources, evolving with a changing landscape where "4,000 advertising messages hit us daily across multiple platforms" as well as aligning with the planet’s needs.

Only a third of ads get the audience’s full attention, according to Dentsu Aegis Network’s research. Whenever people can skip ads, "they often do. And when they cannot skip, they often look away," a recent report by the company posits.

“The explosion in digital content, new forms of advertising and technology at our fingertips has created both the motive and the means for people to screen advertising out of their lives,” it adds.

Doing advertising with the attention economy at the core "means you don't spend energy on any communication that doesn't have [an effective] effect, which literally for energy makes a big change because you can make ads smaller, more targeted, and more relevant at the same time," Huijboom told Euronews Next.

The new world implies a challenge for advertisers, "an ad that is not seen is worthless" and looked at from a sustainability perspective, it is also a waste of resources, he added.

Simple elements like the length of an online video or file size can be manipulated and changed to improve both the attention metric and carbon footprint.

Choosing marketplaces and media owners that have set net-zero, science-based targets and are committed to continuous improvement is also crucial, says Huijboom, adding that agencies should prioritise marketplaces and media owners that have set net-zero science-based targets themselves.

"Of course, we have our own emission targets as a business, but that's only a small thing we can do. The multiplier for our business is really what we can do with our clients in changing that behaviour," he noted.

The third dimension of the sustainability strategy is the "how," which focuses on balancing the carbon footprint with commercial objectives. Again, attention plays a vital role in finding the right balance, and AI can help.

Historically, the advertising industry has been focused "on selling more stuff," says the Dentsu CEO, but "in a world where the resources are finite, you need to take a different approach".

The advertising industry can make a difference by influencing how people think, feel, and act, says Huijboom, and by leveraging this "superpower," advertisers can drive positive change.

"Just think about getting people into electric cars, into plant-based food, into reduced packaging products, into green banking, green pensions… If we are able to make that interesting to people and irresistible, we as an industry can move the needle," he noted.

And "if you make the link, it is very obvious that with generative AI we can have a huge social impact" that is "broader than sustainability".

Source: Euronews

A research team led by Aarhus University, Denmark, in collaboration with researchers from more than 50 research institutes around the world, has assessed how past climate changes have affected how the composition of tree species in one area differs from the composition of neighbouring areas on six continents.

What they have studied is called beta diversity, which you can read about below.*

They found that the global pattern of beta diversity in terms of tree species, species characteristics and evolutionary history was closely linked to temperature changes since the peak of the last ice age, which was about 21,000 years ago. Moreover, they show that the effects of historical climate variations on the beta diversity were stronger than the effects of current climatic conditions.

Most of the tree species

It should be added that the researchers have only studied the angiosperm tree species -- i.e. species that produce seeds enclosed within a carpel. Angiosperms make up about 80 per cent of all plant species, and some of the most common angiosperm tree species are oak, beech, birch, maple, linden, maple, willow, palm, and eucalyptus.

The researchers combined data from five openly shared databases of tree species and their distributions, with information on the phylogenetic relations between species, and their ecomorphological attributes.

Two different effects on forests

They then divided the effects of ancient climate change on different habitats into two components, each with its own technical term:

- Turnover - i.e. changes due to species replacement. If one species goes extinct in a habitat, another species comes in and fills its ecological role. It turns out that the greater the temperature changes an area has experienced since the Ice Age, the less replacement has occurred in that area.

- Nestedness. In beta diversity, this term describes a pattern in which the composition of species in a diverse habitat is a subset of the species composition in a different and less diverse one -- such that the more diverse habitat contains all the species found in the less diverse one, plus additional species. This is an important concept in understanding the organization of biodiversity because it can help identify areas that are more important for conservation. Habitats with nested species compositions may have lower overall biodiversity, but may contain species not found in other habitats, making them essential for preserving overall biodiversity. And the greater the temperature changes an area has experienced, the more nestedness has occurred. Climate fluctuations have thus wiped out local species that have not been replaced.

The authors found that the influence of the two components shifted from the equator to the poles.

In tropical areas, turnover -- i.e. species replacement -- was the most important factor in determining changes in species composition between localities, due to rapid species change.

In temperate regions, nestedness was the primary mechanism for determining changes in species composition, because the species richness declines as we get closer to the poles.

The purpose of the study, which has just been published in Science Advances, is to supply the ecology science with a tool to solve the major challenge of understanding how ongoing and near-future climate change reshapes the distribution of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

"Because the Earth's climate has changed enormously through geological time, exploring the effects of past climate change on current biodiversity provides an opportunity to understand the risks emerging from ongoing and future human-induced climate change," explains the study's first author, Wubing Xu, who initiated the study at Aarhus University and is now a postdoc at the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv).

The researchers point out that the study also provides a new understanding of the challenges to ecosystem protection and management of efforts to mitigate the impacts of such changes.

Crucial roles

"Trees and tree diversity play crucial roles for terrestrial ecosystems, global biodiversity, and humans. This study confirms and extends our previous findings of the high sensitivity of tree diversity to paleoclimatic changes on a global scale. It also suggests that ongoing climate change has the potential to dramatically influence global biodiversity and ecosystem properties not just via direct effects, but also via its effects on trees as ecosystem engineers," emphasizes Professor Jens-Christian Svenning, a co-author of the study.

"I hope these findings can aid the development of conservation and management plans that consider the long-term and diverse impacts of climate change on all biodiversity dimensions. Only then is there a realistic chance that we will reach goal A of Kunming-Montreal's Sustainable Development Goals for 2050," adds Assistant Professor Alejandro Ordonez from Aarhus University and senior author of the study.

(The mentioned goal A for 2050 includes that human induced extinction of known threatened species is halted, and, by 2050, the extinction rate and risk of all species are reduced tenfold.)

*Beta diversity is a measure of the variation of species between different habitats or areas. It helps us understand the diversity of life in a given region or ecosystem by comparing the number and types of species present in different locations.

For example, comparing the number and types of birds in a forest versus grassland, beta diversity will help you understand the differences in bird species between the two environments. It can also help identify regions that have unique or rare species and can be used to monitor changes in biodiversity over time.

Source: Science Daily

The global paper packaging materials market is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.6% over the analysis period from 2022 to 2030, according to a report by Research and Markets.

The report, titled ‘Paper Packaging Materials: Global Strategic Business Report,’ indicates that the market is estimated to have been worth $251.7bn in 2022 and is projected to reach $420.6bn by 2030.

The significance of sustainability continues to be a crucial element

Sustainability remains a critical factor driving recycling initiatives in the global paper packaging materials market, according to the report. The Paper Bags & Sacks segment is expected to record a 6.6% CAGR and reach $132.8bn by the end of the analysis period.

The market in the US is estimated to be worth $66.3bn as of 2022 while China’s market is forecast to grow at a CAGR of 7.7% over the analysis period and reach a projected size of $87.5bn by 2030.

Among the other noteworthy geographic markets are Japan and Canada, which are each forecasted to grow at 5.4% and 5.8%, respectively, over the 2022-2030 period.

The technical challenges associated with sustainable packaging

In Europe, Germany is forecast to grow at approximately 6.1% CAGR. Led by countries such as Australia, India and South Korea, the market in Asia-Pacific is forecast to reach $65.4bn by the year 2030.

Rising environmental concerns regarding the use of plastics in packaging applications are spurring demand for paper. The sustainability factor remains critical in driving recycling initiatives in the paper packaging materials market.

The report also provides an analysis of the technical challenges associated with sustainable packaging.

Ultimately, the global paper packaging materials market is expected to grow significantly in the coming years, driven by sustainability and recycling initiatives.

Source: Mohamed Dabo, Packaging Gateway

The inability to execute, pressured by fewer resources, threatens to compound previous risks, unless executives take the appropriate steps to achieve sustainability.

Sustainability is a critical corporate issue, touching everything from climate change and clean air, to regulatory compliance and brand integrity, says the second annual sustainability survey, conducted by The Harris Poll and sponsored by Google Cloud.

The global survey, which surveyed 1,476 top-level executives in 16 countries, reveals a new hazard: failure to execute. These include greater accountability, better measurement and management, and well-defined leadership.

Executives struggle to prioritise

The research shows that Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) efforts have fallen from the No 1 organisational priority in 2022 to No 3 in 2023. Many executives point to the macroeconomic environment and pressure from external parties to cut corners in their sustainability initiatives and prioritise optimising client relationships and driving revenue.

But looking at sustainability as a short-term cost instead of a long-term investment is a missed opportunity. The vast majority (85%) of executives acknowledge customers are more likely to engage and do business with sustainable brands, but 78% are now forced to achieve sustainability results on less money than before. The motivation is there, with 72% of respondents saying: "Everyone says they want to advance sustainability efforts, but no one knows how to actually do it” — an increase of seven percentage points from last year. With better measurement, clear decision-making and some creativity, companies can better position themselves to progress on their sustainability and business goals.

Overcoming accidental greenwashing

Corporate greenwashing and green hypocrisy remained pervasive concerns among this year’s respondents, with nearly six out of 10 executives (59%) admitting to overstating — or inaccurately representing — their sustainability activities.

Many believe greenwashing is accidental and underscores the need for accurate measurement, identifying a lack of tools as one of the biggest barriers to true progress. Executives are eager for better systems to track their progress, with 87% of respondents looking to incorporate better measurement into their organisations to help make more accurate targets.

Measurement is critical. But coupling accurate measurement tools with more ambitious targets is where we believe there is untapped opportunity.

Driving change in internal structure

In addition to accurate data, achieving an organisation’s sustainability goals requires strong internal teams and structure. The research shows that many executives are also grappling with complex behind-the-scenes logistics of who makes sustainability-related decisions within their company. Most executives (84%) believe their sustainability initiatives would be more effective if they had a better structure with clear accountability. But what does “better” look like?

Many believe greenwashing is accidental and underscores the need for accurate measurement, identifying a lack of tools as one of the biggest barriers to true progress goals.

Continuing to build a sustainable future

Despite headwinds, there’s reason to be optimistic that organisations will continue to operationalise and prioritise sustainability. Nearly all companies (96%) have at least one program in place to advance their sustainability initiatives, and participation in programs remains mostly unchanged from 2022. Interest in organisational sustainability also remains strong, with 84% of respondents saying they care more about sustainability than before. - TradeArabia News Service

Source: Gulf Daily News

A new special category dubbed “Climate Action” has been added to the Zayed Sustainability Prize, the UAE's groundbreaking international award for recognizing excellence in sustainability. This new category aims to recognize and support creative responses to climate change and the preservation of the planet's natural resources.

The introduction of the Climate Action category takes place in conjunction with the UAE's Year of Sustainability, a national program that aims to hasten sustainable development throughout the nation in accordance with the UAE's national policy. Also, it occurs before the COP28, the 28th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which will take place later this year in the UAE.

H.E. Al Jaber added, “In this critical decade of action, the Climate Action category is a significant addition to the Prize's mandate, and we look forward to receiving submissions from around the world. We are proud to encourage and reward innovative solutions needed to turn climate pledges into concrete action, and drive tangible, inclusive and lasting progress for our planet and communities.”

The Zayed Sustainability Prize was established in 2008 as a tribute to the sustainability and humanitarian legacy of the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the Founding Father of the UAE. The Prize recognises organisations and high schools that are delivering impactful, and inspiring innovations across the categories of Health, Food, Energy, Water, Global High Schools and now Climate Action.

The new Climate Action category will further broaden the Prize's reach and impact by rewarding solutions that protect and enhance the natural environment, while also addressing the urgent challenge of climate change. This includes organisations that promote climate adaptation, build resilience and deploy environmental solutions. Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and nonprofit organisations (NPOs) are eligible to apply to the Climate Action category.

The Zayed Sustainability Prize has a 15-year track record of transforming lives by empowering sustainable solutions across health, food, energy and water. Now, through its special Climate Action category, and as the world's efforts to fight climate change grows ever larger, the Prize will help scale innovative solutions that tackle environmental problems and enable communities to build climate resilience.

The Zayed Sustainability Prize has become a global platform for promoting sustainable development, with winners and finalists hailing from all corners of the planet. Today, the Prize celebrates 15 years of global impact with over 378 million people around the world benefiting from its 106 winners' solutions.

The Prize rewards US $600,000 to each winner in the Health, Food, Energy, Water, and Climate Action categories. The Global High Schools category is split into six world regions, with each school able to claim up to US $100,000 to start or further expand their project.

The launch of the Climate Action category is expected to attract a wide range of submissions from around the world. The Zayed Sustainability Prize is calling for entries from nonprofit organisations and small and medium sized enterprises from now until 23 May 2023. The winners will be announced at an awards ceremony in Abu Dhabi.

Source: MENAFN - Asdaf News

The March 20, 2023 release of the final installment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), an eight-year long undertaking from the world’s most authoritative scientific body on climate change. Drawing on the findings of 234 scientists on the physical science of climate change, 270 scientists on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability to climate change, and 278 scientists on climate change mitigation, this IPCC synthesis report provides the most comprehensive, best available scientific assessment of climate change.

It also makes for grim reading. Across nearly 8,000 pages, the AR6 details the devastating consequences of rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions around the world — the destruction of homes, the loss of livelihoods and the fragmentation of communities, for example — as well as the increasingly dangerous and irreversible risks should we fail to change course.

But the IPCC also offers hope, highlighting pathways to avoid these intensifying risks. It identifies readily available, and in some cases, highly cost-effective actions that can be undertaken now to reduce GHG emissions, scale up carbon removal and build resilience. While the window to address the climate crisis is rapidly closing, the IPCC affirms that we can still secure a safe, livable future.

Here are 10 key findings you need to know:

1. Human-induced global warming of 1.1 degrees C has spurred changes to the Earth’s climate that are unprecedented in recent human history.

Already, with 1.1 degrees C (2 degrees F) of global temperature rise, changes to the climate system that are unparalleled over centuries to millennia are now occurring in every region of the world, from rising sea levels to more extreme weather events to rapidly disappearing sea ice.

Additional warming will increase the magnitude of these changes. Every 0.5 degree C (0.9 degrees F) of global temperature rise, for example, will cause clearly discernible increases in the frequency and severity of heat extremes, heavy rainfall events and regional droughts. Similarly, heatwaves that, on average, arose once every 10 years in a climate with little human influence will likely occur 4.1 times more frequently with 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) of warming, 5.6 times with 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and 9.4 times with 4 degrees C (7.2 degrees F) — and the intensity of these heatwaves will also increase by 1.9 degrees C (3.4 degrees F), 2.6 degrees C (4.7 degrees F) and 5.1 degrees C (9.2 degrees F) respectively.

Rising global temperatures also heighten the probability of reaching dangerous tipping points in the climate system that, once crossed, can trigger self-amplifying feedbacks that further increase global warming, such as thawing permafrost or massive forest dieback. Setting such reinforcing feedbacks in motion can also lead to other substantial, abrupt and irreversible changes to the climate system. Should warming reach between 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and 3 degrees C (5.4 degrees F), for example, the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets could melt almost completely and irreversibly over many thousands of years, causing sea levels to rise by several meters.

2. Climate impacts on people and ecosystems are more widespread and severe than expected, and future risks will escalate rapidly with every fraction of a degree of warming.

Described as an “an atlas of human suffering and a damning indictment of failed climate leadership” by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, one of AR6’s most alarming conclusions is that adverse climate impacts are already more far-reaching and extreme than anticipated. About half of the global population currently contends with severe water scarcity for at least one month per year, while higher temperatures are enabling the spread of vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, West Nile virus and Lyme disease. Climate change has also slowed improvements in agricultural productivity in middle and low latitudes, with crop productivity growth shrinking by a third in Africa since 1961. And since 2008, extreme floods and storms have forced over 20 million people from their homes every year.

Every fraction of a degree of warming will intensify these threats, and even limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degree C is not safe for all. At this level of warming, for example, 950 million people across the world’s drylands will experience water stress, heat stress and desertification, while the share of the global population exposed to flooding will rise by 24%.

Similarly, overshooting 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F), even temporarily, will lead to much more severe, oftentimes irreversible impacts, from local species extinctions to the complete drowning of salt marshes to loss of human lives from increased heat stress. Limiting the magnitude and duration of overshooting 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F), then, will prove critical in ensuring a safe, livable future, as will holding warming to as close to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) or below as possible. Even if this temperature limit is exceeded by the end of the century, the imperative to rapidly curb GHG emissions to avoid higher levels of warming and associated impacts remains unchanged.

3. Adaptation measures can effectively build resilience, but more finance is needed to scale solutions.

Climate policies in at least 170 countries now consider adaptation, but in many nations, these efforts have yet to progress from planning to implementation. Measures to build resilience are still largely small-scale, reactive and incremental, with most focusing on immediate impacts or near-term risks. This disparity between today’s levels of adaptation and those required persists in large part due to limited finance. According to the IPCC, developing countries alone will need $127 billion per year by 2030 and $295 billion per year by 2050 to adapt to climate change. But funds for adaptation reached just $23 billion to $46 billion from 2017 to 2018, accounting for only 4% to 8% of tracked climate finance.

The good news is that the IPCC finds that, with sufficient support, proven and readily available adaptation solutions can build resilience to climate risks and, in many cases, simultaneously deliver broader sustainable development benefits.

Ecosystem-based adaptation, for example, can help communities adapt to impacts that are already devastating their lives and livelihoods, while also safeguarding biodiversity, improving health outcomes, bolstering food security, delivering economic benefits and enhancing carbon sequestration. Many ecosystem-based adaptation measures — including the protection, restoration and sustainable management of ecosystems, as well as more sustainable agricultural practices like integrating trees into farmlands and increasing crop diversity — can be implemented at relatively low costs today. Meaningful collaboration with Indigenous Peoples and local communities is critical to the success of this approach, as is ensuring that ecosystem-based adaptation strategies are designed to account for how future global temperature rise will impact ecosystems.

4. Some climate impacts are already so severe they cannot be adapted to, leading to losses and damages.

Around the world, highly vulnerable people and ecosystems are already struggling to adapt to climate change impacts. For some, these limits are “soft” — effective adaptation measures exist, but economic, political and social obstacles constrain implementation, such as lack of technical support or inadequate funding that does not reach the communities where it’s needed most. But in other regions, people and ecosystems already face or are fast approaching “hard” limits to adaptation, where climate impacts from 1.1 degrees C (2 degrees F) of global warming are becoming so frequent and severe that no existing adaptation strategies can fully avoid losses and damages. Coastal communities in the tropics, for example, have seen entire coral reef systems that once supported their livelihoods and food security experience widespread mortality, while rising sea levels have forced other low-lying neighborhoods to move to higher ground and abandon cultural sites.

Whether grappling with soft or hard limits to adaptation, the result for vulnerable communities is oftentimes irreversible and devastating. Such losses and damages will only escalate as the world warms. Beyond 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) of global temperature rise, for example, regions reliant on snow and glacial melt will likely experience water shortages to which they cannot adapt. At 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F), the risk of concurrent maize production failures across important growing regions will rise dramatically. And above 3 degrees C (5.4 degrees F), dangerously high summertime heat will threaten the health of communities in parts of southern Europe.

Urgent action is needed to avert, minimize and address these losses and damages. At COP27, countries took a critical step forward by agreeing to establish funding arrangements for loss and damage, including a dedicated fund. While this represents a historic breakthrough in the climate negotiations, countries must now figure out the details of what these funding arrangements, as well as the new fund, will look like in practice — and it’s these details that will ultimately determine the adequacy, accessibility, additionality and predictability of these financial flows to those experiencing loss and damage.

5. Global GHG emissions peak before 2025 in 1.5 degrees C-aligned pathways.

The IPCC finds that there is a more than 50% chance that global temperature rise will reach or surpass 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) between 2021 and 2040 across studied scenarios, and under a high-emissions pathway, specifically, the world may hit this threshold even sooner — between 2018 and 2037. Global temperature rise in such a carbon-intensive scenario could also increase to 3.3 degrees C to 5.7 degrees C (5.9 degrees F to 10.3 degrees F) by 2100. To put this projected amount of warming into perspective, the last time global temperatures exceeded 2.5 degrees C (4.5 degrees F) above pre-industrial levels was more than 3 million years ago.

Changing course to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) — with no or limited overshoot — will instead require deep GHG emissions reductions in the near-term. In modelled pathways that limit global warming to this goal, GHG emissions peak immediately and before 2025 at the latest. They then drop rapidly, declining 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035, relative to 2019 levels.

While there are some bright spots — the annual growth rate of GHG emissions slowed from an average of 2.1% per year between 2000 and 2009 to 1.3% per year between 2010 and 2019, for example — global progress in mitigating climate change remains woefully off track. GHG emissions have climbed steadily over the past decade, reaching 59 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) in 2019 — approximately 12% higher than in 2010 and 54% greater than in 1990.

Even if countries achieved their climate pledges (also known as nationally determined contributions or NDCs), WRI research finds that they would reduce GHG emissions by just 7% from 2019 levels by 2030, in contrast to the 43% associated with limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F). And while handful of countries have submitted new or enhanced NDCs since the IPCC’s cut-off date, more recent analysis that takes these submissions into account finds that these commitments collectively still fall short of closing this emissions gap.

6. The world must rapidly shift away from burning fossil fuels — the number one cause of the climate crisis.

In pathways limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) with no or limited overshoot just a net 510 GtCO2 can be emitted before carbon dioxide emissions reach net zero in the early 2050s. Yet future carbon dioxide emissions from existing and planned fossil fuel infrastructure alone could surpass that limit by 340 GtCO2, reaching 850 GtCO2.

A mix of strategies can help avoid locking in these emissions, including retiring existing fossil fuel infrastructure, canceling new projects, retrofitting fossil-fueled power plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies and scaling up renewable energy sources like solar and wind (which are now cheaper than fossil fuels in many regions).

In pathways that limit warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) — with no or limited overshoot — for example, global use of coal falls by 95% by 2050, oil declines by about 60% and gas by about 45%. These figures assume significant use of abatement technologies like CCS, and without them, these same pathways show much steeper declines by mid-century. Global use of coal without CCS, for example, is virtually phased out by 2050.

Although coal-fired power plants are starting to be retired across Europe and the United States, some multilateral development banks continue to invest in new coal capacity. Failure to change course risks stranding assets worth trillions of dollars.

7. We also need urgent, systemwide transformations to secure a net-zero, climate-resilient future.

While fossil fuels are the number one source of GHG emissions, deep emission cuts are necessary across all of society to combat the climate crisis. Power generation, buildings, industry, and transport are responsible for close to 80% of global emissions while agriculture, forestry and other land uses account for the remainder.

Take the transport system, for instance. Drastically cutting emissions will require urban planning that minimizes the need for travel, as well as the build-out of shared, public and nonmotorized transport, such as rapid transit and bicycling in cities. Such a transformation will also entail increasing the supply of electric passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles and buses, coupled with wide-scale installation of rapid-charging infrastructure, investments in zero-carbon fuels for shipping and aviation and more.

Policy measures that make these changes less disruptive can help accelerate needed transitions, such as subsidizing zero-carbon technologies and taxing high-emissions technologies like fossil-fueled cars. Infrastructure design — like reallocating street space for sidewalks or bike lanes — can help people transition to lower-emissions lifestyles. It is important to note there are many co-benefits that accompany these transformations, too. Minimizing the number of passenger vehicles on the road, in this example, reduces harmful local air pollution and cuts traffic-related crashes and deaths.

Transformative adaptation measures, too, are critical for securing a more prosperous future. The IPCC emphasizes the importance of ensuring that adaptation measures drive systemic change, cut across sectors and are distributed equitably across at-risk regions. The good news is that there are oftentimes strong synergies between transformational mitigation and adaptation. For example, in the global food system, climate-smart agriculture practices like shifting to agroforestry can improve resilience to climate impacts, while simultaneously advancing mitigation.

8. Carbon removal is now essential to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C.

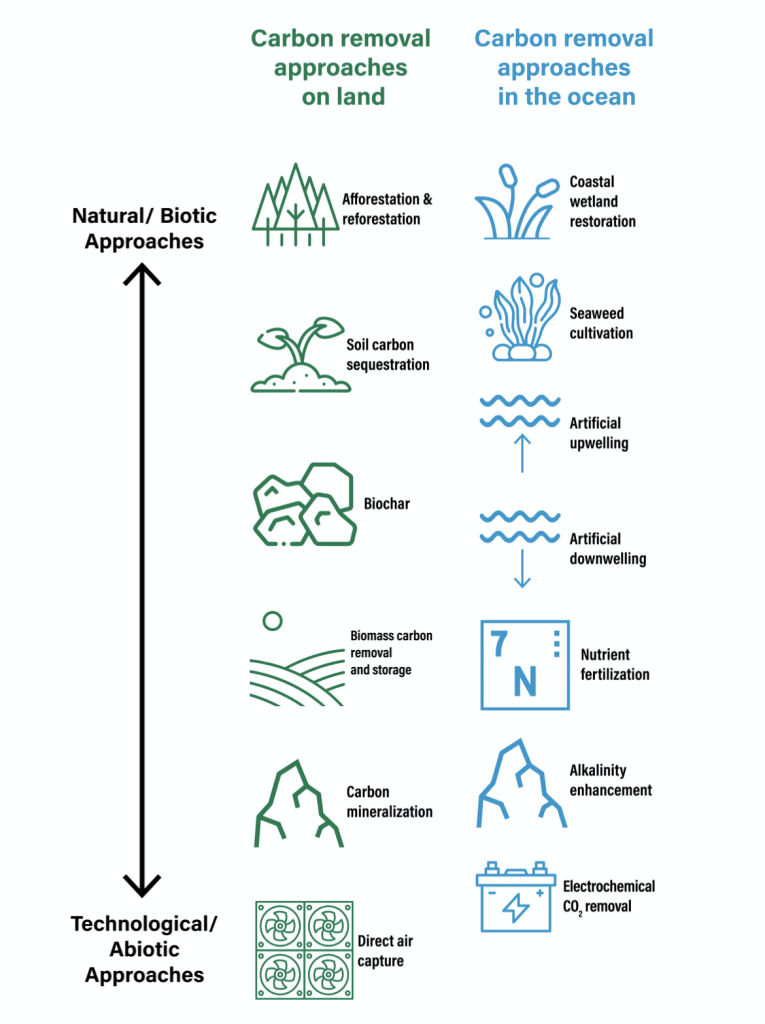

Deep decarbonization across all systems while building resilience won’t be enough to achieve global climate goals, though. The IPCC finds that all pathways that limit warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) — with no or limited overshoot — depend on some quantity of carbon removal. These approaches encompass both natural solutions, such as sequestering and storing carbon in trees and soil, as well as more nascent technologies that pull carbon dioxide directly from the air.

Note: This figure includes carbon removal approaches mentioned in countries’ LTSs as well as other leading proposed approaches.

Note: The natural vs. technological categorization shown here is illustrative rather than definitive and will vary depending on how approaches are applied, particularly for carbon removal approaches in the ocean.

The amount of carbon removal required depends on how quickly we reduce GHG emissions across other systems and the extent to which climate targets are overshot, with estimates ranging from between 5 GtCO2 to 16 GtCO2 per year needed by mid-century.

All carbon removal approaches have merits and drawbacks. Reforestation, for instance, represents a readily available, relatively low-cost strategy that, when implemented appropriately, can deliver a wide range of benefits to communities. Yet the carbon stored within these ecosystems is also vulnerable to disturbances like wildfires, which may increase in frequency and severity with additional warming. And, while technologies like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) may offer a more permanent solution, such approaches also risk displacing croplands, and in doing so, threatening food security. Responsibly researching, developing and deploying emerging carbon removal technologies, alongside existing natural approaches, will therefore require careful understanding of each solution’s unique benefits, costs and risks.

9. Climate finance for both mitigation and adaptation must increase dramatically this decade.

The IPCC finds that public and private finance flows for fossil fuels today far surpass those directed toward climate mitigation and adaptation. Thus, while annual public and private climate finance has risen by upwards of 60% since the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report, much more is still required to achieve global climate change goals. For instance, climate finance will need to increase between 3 and 6 times by 2030 to achieve mitigation goals, alone.

This gap is widest in developing countries, particularly those already struggling with debt, poor credit ratings and economic burdens from the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent mitigation investments, for example, need to increase by at least sixfold in Southeast Asia and developing countries in the Pacific, fivefold in Africa and fourteenfold in the Middle East by 2030 to hold warming below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F). And across sectors, this shortfall is most pronounced for agriculture, forestry and other land use, where recent financial flows are 10 to 31 times below what is required to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals.

Finance for adaptation, as well as loss and damage, will also need to rise dramatically. Developing countries, for example, will need $127 billion per year by 2030 and $295 billion per year by 2050. While AR6 does not assess countries’ needs for finance to avert, minimize and address losses and damages, recent estimates suggest that they will be substantial in the coming decades. Current funds for both fall well below estimated needs, with the highest estimates of adaptation finance totaling under $50 billion per year.

10. Climate change — as well as our collective efforts to adapt to and mitigate it — will exacerbate inequity should we fail to ensure a just transition.

Households with incomes in the top 10%, including a relatively large share in developed countries, emit upwards of 45% of the world's GHGs, while those families earning in the bottom 50% account for 15% at most. Yet the effects of climate change already — and will continue to — hit poorer, historically marginalized communities the hardest.

Today, between 3.3 billion and 3.6 billion people live in countries that are highly vulnerable to climate impacts, with global hotspots concentrated in the Arctic, Central and South America, Small Island Developing states, South Asia and much of sub-Saharan Africa. Across many countries in these regions, conflict, existing inequalities and development challenges (e.g., poverty and limited access to basic services like clean water) not only heighten sensitivity to climate hazards, but also limit communities’ capacity to adapt. Mortality from storms, floods and droughts, for instance, was 15 times higher in countries with high vulnerability to climate change than in those with very low vulnerability from 2010 to 2020.

At the same time, efforts to mitigate climate change also risk disruptive changes and exacerbating inequity. Retiring coal-fired power plants, for instance, may displace workers, harm local economies and reconfigure the social fabric of communities, while inappropriately implemented efforts to halt deforestation could heighten poverty and intensify food insecurity. And certain climate policies, such as carbon taxes that raise the cost of emissions-intensive goods like gasoline, can also prove to be regressive, absent of efforts to recycle the revenues raised from these taxes back into programs that benefit low-income communities.

Fortunately, the IPCC identifies a range of measures that can support a just transition and help ensure that no one is left behind as the world moves toward a net-zero-emissions, climate-resilient future. Reconfiguring social protection programs (e.g., cash transfers, public works programs and social safety nets) to include adaptation, for example, can reduce communities’ vulnerability to a wide range of future climate impacts, while strengthening justice and equity. Such programs are particularly effective when paired with efforts to expand access to infrastructure and basic services.

Similarly, policymakers can design mitigation strategies to better distribute the costs and benefits of reducing GHG emissions. Governments can pair efforts to phase out coal-fired electricity generation, for instance, with subsidized job retraining programs that support workers in developing the skills needed to secure new, high-quality jobs. Or, in another example, officials can couple policy interventions dedicated to expanding access to public transit with interventions to improve access to nearby, affordable housing.

Across both mitigation and adaptation measures, inclusive, transparent and participatory decision-making processes will play a central role in ensuring a just transition. More specifically, these forums can help cultivate public trust, deepen public support for transformative climate action and avoid unintended consequences.

Looking Ahead

The IPCC’s AR6 makes clear that risks of inaction on climate are immense and the way ahead requires change at a scale not seen before. However, this report also serves as a reminder that we have never had more information about the gravity of the climate emergency and its cascading impacts — or about what needs to be done to reduce intensifying risks.

Limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) is still possible, but only if we act immediately. As the IPCC makes clear, the world needs to peak GHG emissions before 2025 at the very latest, nearly halve GHG emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero CO2 emissions around mid-century, while also ensuring a just and equitable transition. We’ll also need an all-hands-on-deck approach to guarantee that communities experiencing increasingly harmful impacts of the climate crisis have the resources they need to adapt to this new world. Governments, the private sector, civil society and individuals must all step up to keep the future we desire in sight. A narrow window of opportunity is still open, but there’s not one second to waste.

Source: Sophie Boehm and Clea Schumer, World Resources Institute

The average life span of a commercial jet is about 25 years, and something like 12,000 of them and other aircraft are expected to reach the end of life in the next two decades. That’s an average of about 600 airplanes each year. What happens to all those planes when they are no longer economically viable and ready to come out of service?

“The retirement of commercial jets is a complex process that requires careful planning and execution. However, it also presents an opportunity for the aviation industry to reduce waste and lower costs through the reuse and recycling of valuable parts. In recent years, the practice of upcycling airplane parts has gained significant momentum. This innovative approach involves repurposing old materials to create unique and innovative products.” – explains Toma Matutyte, CEO Locatory.com Marketplace.

Upcycling is a sustainable and eco-friendly way to reduce waste and minimize the environmental impact of discarded materials. By transforming airplane parts into new and exciting items, we can breathe new life into these materials and give them a second chance to shine.

Fuselages can become conference tables. Cowlings, the metal coverings of an engine, can be made into beds. Wings turned into dramatic, one-of-a-kind corporate executive desks. Windows – transformed into mirrors. From furniture to home decor, upcycling airplane parts has opened up a world of possibilities for creative designers and artisans. The unique shapes and textures of these materials lend themselves to a wide range of applications, making them a popular choice for those looking to create one-of-a-kind pieces.

“Recycling aircraft parts has been a long-standing practice in the aviation industry. For years, parts have been refurbished to fit on other aircraft or repurposed to create different products, such as circuit boards. This has been the industry standard, as reported by the Aircraft Fleet Recycling Association (AFRA). In fact, AFRA estimates that approximately 80% to 85% of aircraft parts are recycled when an aircraft reaches retirement.

“Despite this, the aviation industry is constantly seeking new and innovative ways to reuse aircraft parts. As sustainability becomes an increasingly important issue, alternative ideas for repurposing these parts are becoming more commonplace.” – says, Toma Matutyte, CEO Locatory.com Marketplace.

From the Sky to Your Living Room: Turning Aircraft Parts into Designer Furniture

Airbus and Lufthansa are leading the way in transforming retired aircraft parts into stylish homeware collections. The project, called A Piece of Sky, was initiated by Airbus and its Airbus BizLab program, and has resulted in the creation of armchairs, coffee tables, and lamps made from cabin windows and test flight storage data modules. The company has even produced Airbus-branded surfboards made from recycled carbon.

Lufthansa also joined the trend by launching its Upcycling Collection 2.0. This range of homeware products includes furniture, sculptures, and accessories made from retired aircraft parts, such as a flying coffee table created from landing flaps and a wall bar made from an airplane window mounted onto a wooden box.

These innovative collections not only breathe new life into retired aircraft parts but also offer a unique and sustainable way to decorate modern living spaces. By repurposing these materials, Airbus and Lufthansa are setting an example for other companies to follow in creating environmentally friendly and stylish homeware collections.

Up in the Air: Aviation-Themed Accommodations

Ideal for aviation enthusiasts or those looking for something a little bit different. Converted Boeing 747, located at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm. This aviation-themed hotel offers the chance to sleep in a jet without leaving the ground.

The real highlight of this hotel is the Cockpit Suite, which features a fully preserved flight deck complete with all the original instruments. You can live out your pilot dreams and feel like you’re flying the plane yourself!

From Planes to Trees: Christmas Decorations with Aircraft Components

With a variety of parts available, including washers, fasteners, rivets, hinges, grommets, and seals, repurposing them is a breeze. All you need is some ribbon or colored string to tie them onto your tree.

So why not give it a try and see how your tree can take flight with a touch of aviation-inspired flair.

Jet-Set Selfies: Get Ready for the Ultimate Photoshoot Experience

Have you ever dreamed of soaring through the skies on a private jet? While it may not be a reality for most of us, there’s a fun and lighthearted way to experience the high life. Head over to the Selfie Factory at the O2 in London, where you can indulge in a day of make-believe and capture some amazing photos.

The Selfie Factory boasts a range of themed sets, including a luxurious private jet interior. You can snap as many photos as you like.

Sip on Sustainability: Drinks Bars Made from Aircraft Scrap

Raise a glass at your very own custom-built bar that’s been crafted out of upcycled aircraft fuselage. Cheers!

“Upcycling: Transforming Scrap into Stunning Creations! In addition to traditional recycling, a new and exciting market is emerging – one that breathes new life into old parts and transforms them into stunning creations: upcycling. The possibilities are endless, and creativity knows no bounds. Entire aircraft are being converted into luxurious apartments or hotels, while smaller “aeropods” made from fuselage sections are being used as charming conservatories or gazebos. Various companies are also offering unique furniture, as well as stylish bags and accessories crafted from seat covers and life jackets.” says, Toma Matutyte, CEO Locatory.com Marketplace.

Upcycling is a fantastic way to reduce waste and give old materials a new lease on life. It’s a sustainable and eco-friendly approach that not only benefits the environment but also allows for the creation of one-of-a-kind pieces that are both functional and beautiful. So, whether you’re looking to add a touch of aviation-inspired style to your home or office, or simply want to do your part for the planet, upcycling is the way to go!

Source: Avia Solutions Group, AeroTime Hub

Dynamic computer models of cities known as ‘digital twins’ could help drive sustainable development across the world’s urban areas, an international team of authors argues in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Digital twins are more than just static models. They incorporate near-real-time data from sensors and other sources to produce “virtual replicas,” the authors explain—“in silico equivalents of real-world objects.”

The concept of digital twins first arose in manufacturing, and they are primarily used in product and process engineering. But the models have also been employed in fields ranging from personalized medicine to climate forecasting, at scales from the molecular to the planetary.

Many researchers have posited that digital twins will be a powerful tool for sustainability efforts. But nobody has taken a rigorous look at the benefits and pitfalls of urban digital twins. The new study takes on that task, paying particular attention to the potential for the modeling approach to help achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Digital twins have a variety of potential benefits in this realm, the researchers say. They can help cities allocate resources more efficiently—design more effective water grids, predict traffic congestion to guide transportation planning, simulate consumer behavior to recommend energy-saving measures, and so on.

In addition, “In silico models provide a virtual space where new clean technologies, which promise resource efficiency but may cause unintended harm, can be tested at a speed and scale that may otherwise be inhibited by the precautionary principle,” the researchers write. For example, they could help cities figure out how to incorporate renewable sources of energy into the grid without compromising reliability.

Digital twins could also help scientists and policymakers to collaborate across disciplines, agencies, levels of government, and geographic distances. And they could aid cities in monitoring and reporting progress on the Sustainable Development Goals or other sustainability aims.

Some of the authors of the paper have been involved in the development of a digital twin for Fishermans Bend, an urban renewal project in Melbourne, Australia. The model includes more than 1,400 layers of both historical and real-time data from public and private sources. More than 20 government agencies and municipalities are using the model to analyze how proposed buildings will affect sunlight falling on open space and vegetation, forecast tram traffic patterns, and address other planning questions.

Digital twin models are also being used in cities including Zurich, Singapore, and Shanghai to monitor noise and pollution and facilitate urban planning that takes into account population growth and climate change.

But there are pitfalls to the digital twin approach, too. Because they require so much data, advanced computing power, and technological know-how, digital twins have the potential to exacerbate digital divides, especially between high-income and lower-income countries.

What’s more, even the most complex model may fall short in representing the multifarious nature of a real-life city. The data necessary to underpin a successful digital twin may be unavailable, inaccessible, or incompatible with other sources. And the social-science aspects of digital twins are especially poorly understood.

Finally, models can be optimized for the wrong targets. There are inherent contradictions between different Sustainable Development Goals, and programmers have to take care about how outcomes and parameters are prioritized, the researchers say. For whom and by whom are these decisions made—and who’s left out of the process?

To avoid these pitfalls of digital twins—and reap the potential benefits, the researchers recommend that governments and international institutions get involved in bridging digital divides; leaving digital twin technology to the marketplace virtually guarantees that low-resource countries will be left behind.

They also call on those creating and implementing digital twins of cities to pay attention to social and ethical responsibility. “A central question that derives from these issues is: to what extent are those who may be affected by the decisions based on simulation models included in their design and deployment?” they write.

“Interestingly in such instances, digital twins themselves can raise awareness among planners and policymakers of socioeconomic inequalities, thereby becoming instruments of inclusion,” the researchers add.

Source: Sarah DeWeerdt, Anthropocene

Many product innovations today aim to solve our world’s most pressing issues. Photovoltaic modules, for example, allow us to exploit solar energy to accelerate our decarbonisation efforts and achieve net zero. Like photovoltaic modules, all product innovations have a definite shelf life and eventually become waste, unless they participate in the circular economy. Unfortunately, with a global circularity rate of only 7.2%, most products are discarded as waste.

Without significant changes to the status quo, future product innovations will face difficulty participating in the circular economy. They will pollute our terrestrial ecosystem after they have fulfilled their purpose. They will also indirectly encourage further material production and extraction of the Earth’s resources, emiting immense amounts of greenhouse gases in the process. These ramifications negatively impact the environment and human health and will severely diminish an innovation’s contribution to society.

Conversely, if we could recover, treat and circulate the materials back into our ecosystem, we could mitigate these adverse impacts while generating economic returns. For these reasons, we must prepare our future product innovations for participation in the circular economy. Designing innovations for the circular economy, however, requires deep interdisciplinary knowledge and expertise, which most businesses lack. Consequently, we developed the LASER framework, in consultation with domain experts and leaders, to eliminate the learning curve and empower innovators to design their innovations for the circular economy.

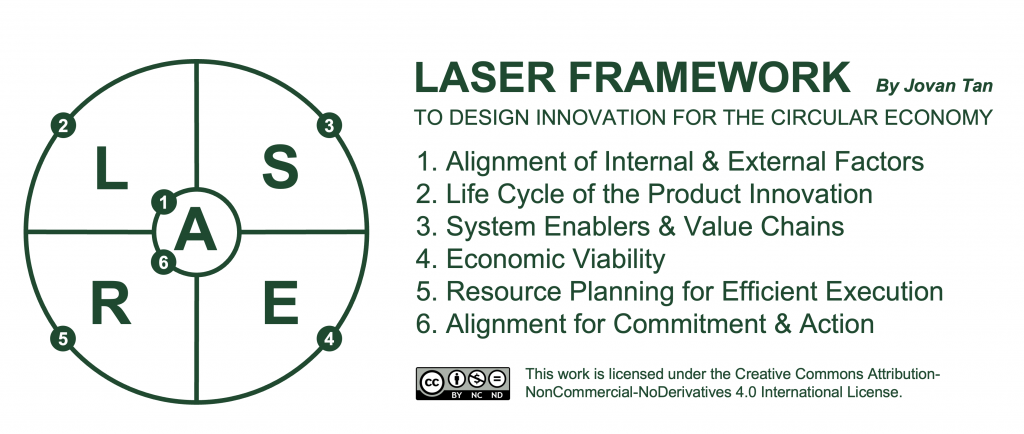

The LASER Framework, for assessing circular economy participation

The LASER framework is a systematic six step framework. It enables innovators to be 'LASER-focused' on working through the key aspects determining whether their proposed innovation can participate in the circular economy. Each letter in the acronym 'LASER' represents an equally important aspect. Innovators are encouraged to work through each step successively. They are encouraged to continuously reiterate and optimise steps two to four until the desired outcome is achieved before constructing an execution plan (step five).

Step 1: Alignment of internal and external factors

The first step of the LASER framework is alignment, both internally within the organization and externally within the macro environment. Internal alignment is achieved when the innovator secures its key stakeholders' acceptance, willingness and commitment to exploring means of designing its product innovations for participation in the circular economy. External alignment refers to supportive and complementary policies, regulations and megatrends in environments where these proposed innovations will be adopted.

Alignment is the bedrock of the LASER framework. Without securing alignment, any innovation endeavour risks a high possibility of incompletion or failure. To increase one’s chance of securing alignment, innovators should consider aligning their intentions with the company’s vision and key business objectives.

Step 2: Life cycle of the product innovation

The second step refers to the product’s material lifecycle. In this step, innovators must evaluate the end-to-end product lifecycle for its material and technological feasibility to participate in the circular economy. Ideally, the used product should be collected, treated and returned to its original state for safe reintroduction into the ecosystem. This perfect closed-loop system, however, may not be realistic today. Therefore, at the very least, innovators must demonstrate their proposed innovation’s circularity pathway through waste valorisation and industrial symbiosis. Employing cradle-to-cradle design principles, such as mono-materialising techniques, can help innovators achieve the latter. Whenever possible, innovators should also comprehensively assess and factor the carbon footprint of their proposed innovation into their decision.

Step 3: System enablers and value chains

An entire value chain is intricately involved to ensure materials can circulate within the ecosystem. Unless the innovator has the resources to organize and maintain a closed-loop ecosystem for its innovation, it needs to work with strategic partners to enable these critical components of the value chain – e.g. suppliers, waste collectors, treatment facilities and off-takers. Therefore, in the third step of the LASER framework, the innovator must identify its critical enablers to achieve success. It must also consider all aspects of the strategic partnership and devise a mutually beneficial plan to secure participation.

Step 4: Economic viability

The result from steps 2 and 3 of the LASER framework is a draft blueprint of how the proposed innovation will participate in the circular economy. The next step is to evaluate this blueprint's unit economics and viability. This crucial step grants the innovator and key stakeholders visibility on the associated revenues and costs per unit. Innovators and critical stakeholders should optimise steps two and three to achieve their desired unit economics. For situations where an optimal combination could not be reached, the innovator can consider introducing additional layers of innovations – such as business models or process innovations – to create and extract untapped value to improve the unit's economics and viability.

Step 5: Resource planning for efficient execution

After achieving an optimised blueprint, the next step is to devise an execution plan outlining how to bring the proposed innovation to market. As with any typical project execution plan, the critical resources needed (workforce, investment, etc.) and the schedules, milestones, risks and impacts should be detailed. Additionally, being mindful of the overarching objective to reduce the resource burden on society and encourage circularity, the plan must embody the prudent and efficient use of resources.

Step 6: Alignment for commitment and action

Finally, with a well-defined blueprint and action plan, innovators should revisit their critical internal stakeholders from step one and seek their concurrence to act and introduce the proposed innovation to the market.

To conclude, business leaders have an innate desire to better our society. They are actively exploring ways to improve the sustainability performance of their product offerings and organizations. However, specialised knowledge is often the most significant obstacle deterring them from achieving it. Hence, we worked with domain experts and leaders to develop a straightforward and simple-to-use framework for innovators to quickly assess and calibrate the circularity performance of their proposed innovations. Introducing this framework will inspire more innovators to design purposeful innovations for the circular economy.

Source: Jovan Tan, World Economic Forum