The 13-day Greening Education Hub, themed ‘Legacy from the Land of Zayed’, marked the end of its activities during COP28.

Hosted by the Ministry of Education, this first-of-its-kind Hub in the history of COP showcased education's vital role in addressing the global climate crisis and achieving sustainable development goals on a global scale. It attracted a diverse audience from different backgrounds and age groups, including a significant number of international visitors.

Dr. Ahmad Belhoul Al Falasi, Minister of Education, said, “As we embarked on the launch of the Legacy from the Land of Zayed Hub, our goal was to make significant advancements in promoting climate education to address the global climate crisis. We aimed to establish a lasting legacy that could serve as a foundation for positive changes throughout the educational process, all the way to building green societies.

The Hub has successfully achieved its objectives. The UAE has inspired educational leaders to implement tangible measures, positioning education at the forefront of worldwide conversations about climate and sustainability. This supports the aim of enhancing the skills of educational cadres, raising environmental and climate awareness among students, and empowering them to become advocates for sustainability in their communities and workplaces."

Dr. Al Falasi added, “As the activities of the Greening Education Hub - Legacy from the Land of Zayed end, we simultaneously embark on a new phase. This involves ongoing collaboration with our local and international partners to underscore the importance of sustainability in the global education sector. We will achieve this through global initiatives, programmes, and partnerships, solidifying our nation's leading role in climate action and striving to create a sustainable future for generations to come."

During COP28, the First Annual Meeting of the Greening Education Partnership, which was held at the Greening Education Hub, issued a Declaration on the Common Agenda for Education and Climate Change at COP28. Through this declaration, member states of the Green Education Partnership pledged to develop national education strategies to mitigate the repercussions of climate change and to leverage the role of education to achieve net-zero emissions in the education sector.

The declaration also highlighted the member states’ pledge to enhance cooperation in all fields to provide domestic and international funding. This is to promote climate education in a way that helps bridge the gap between the current reality and climate targets.

Additionally, during the International Greening Education Ministerial Meeting, which the UAE chaired, the Ministry of Education launched two initiatives in cooperation with UNESCO. The first called for the establishment of an open-source platform on the internet to facilitate access to resources and information and exchange experiences and expertise, in order to support the adoption of green education around the world. The second initiative called for launching a ‘Sustainability Tracking Tool for Educational Institutions’ that contributes to unifying international efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of educational institutions around the world in preparation for COP29.

Furthermore, the Greening Education Hub introduced various initiatives and programmes with the goal of endorsing and fostering the implementation of green education on a global scale.

The Ministry cooperated with the Office for Climate Education and Alef Education, to unveil the Educators’ Voice platform. The initiative aims to enhance green education resources accessible to teachers and educational officials globally through open sources, empowering them to advance their climate readiness.

All Net-Zero Heroes also actively engaged in programmes offered by the Greening Education Hub that were tailored to their respective ages and interests. Each child had the opportunity to participate in approximately 15 events and workshops, assuming various roles in key speaker sessions, including ones involving a dialogue with children from the Arab world that was supported by the Supreme Council for Motherhood and Childhood.

They also took part in discussions, including a ministerial retreat, and served as primary spokespeople representing the children of the UAE during a ceremony honouring educators. Additionally, workshops specifically designed for these heroes were conducted, covering activities such as the ‘My Home’ awareness game sponsored by the Ras Al Khaimah Municipality, a simulation session for COP28, and an appreciation ceremony to celebrate their accomplishments.

The Ministry of Education, through the Greening Education Hub, has made significant progress in attaining the objectives of the four pillars of the Green Education Partnership. Currently, 52% of schools and 36% of universities have enrolled in greening programmes, preparing for official environmental accreditation. Furthermore, all schools across the country now have access to green resources and curricula essential for promoting environmental education.

In terms of greening capacities, the Ministry is actively involved in providing climate training and qualification for one educational official and two teachers in each school nationwide. The initial phase of training for 100 master trainers has been completed, with over 1,400 educational officials and more than 10,000 teachers enrolled in training programmes to enhance their capabilities in green education.

To amplify the role of education in fostering greening communities, the Ministry has devised seven distinct business models for each of the country's emirates. The objective is to boost community engagement with climate education initiatives.

In line with its belief in the power of partnerships in bringing about sustainable change in the educational sector, the Ministry of Education signed two Memoranda of Understanding during COP28. The first MoU was with the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC), which was aimed at developing and implementing initiatives to educate youth and students about environmental protection. The objective is to emphasise their role in shouldering responsibilities, with a focus on preserving wildlife and natural habitats, fostering understanding, and promoting sustainable behavioural change.

Additionally, the Ministry has entered into agreements with the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment as well as with Bayanat. These agreements aim to bolster and advance sustainable scientific and research initiatives, including the initiation of a grant for collaborative research programmes throughout 2024.

The Greening Education Hub – Legacy from the Land of Zayed witnessed an impressive turnout during COP28, with over 50,000 visitors, surpassing expectations by over 270%.

Notably, student and academic engagement with the Hub's activities was exceptional, with more than 3,500 students from 122 schools across the country visiting over the course of 13 days. The Hub played host to 250 panel discussions and workshops, featuring the participation of over 1,000 speakers from more than 50 countries and the attendance of more than 10,000 guests.

Source: WAM

The company targets to diminish greenhouse gas emissions by 17% by 2025

UAE’s IFFCO, the leading FMCG multinational, has allocated AED 77 million to sustainability initiatives over two years, with ten programmes comprising 156 projects in the pipeline.

The company has identified six crucial areas in which it aims to make tangible efforts to boost its environmental performance – climate change, energy management, water management, forests, circular economy, and biodiversity.

To contribute to the global fight against climate change, IFFCO has set a goal to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in its own operations and energy consumption by 17% by 2025, in comparison to its 2021 figures.

The company has analysed its corporate footprint, determining hotspots and key measures to be taken. It will announce detailed targets for 2030 at COP28 (the 28th UN Climate Change Conference), scheduled in Dubai.

Sustainable value-added products

“In line with our vision to become the preferred provider of sustainable value-added products and services for everyone, everywhere and every day, we have adopted a holistic approach to sustainability,” noted Shiraz Allana, Supervisory Board Member at IFFCO.

As part of its Zero Deforestation ambition, IFFCO has achieved 100% traceability to mill (TTM) and 85% traceability to plantation (TTP) for palm oil products.

In the UAE, the company launched the first plant-based meat alternatives factory in the Middle East under the THRYVE™ brand. This 100% greenfield investment aligns with IFFCO’s mission to lead the much-needed diet shift towards more sustainable plant-based proteins.

The company is also working to reduce waste generation and introduce packaging with a reduced environmental impact.

Among corporate sustainability professionals, I often hear a behind-the-scenes code phrase: “We’re not Patagonia.” I’m doing the best I can, it implies, but:

…our business was built on a model that is fundamentally bad for the environment.

…our customers will buy our products regardless of how sustainable they are.

…our impact on nature is far away and indirect.

…paying our workers more would threaten profitability.

…truly engaging with communities is expensive and risky.

…company leadership and investors aren’t bought in.

…pushing any harder could endanger my job.

It’s a catch-all for the reasons a company can’t or won’t transform anything from products to packaging to marketing to supply chains to lobbying. And the number of times I’ve heard variations of it in my 20 years in the field is both a testament to Patagonia’s continued leadership as well as an indication of why businesses are not delivering on sustainability commitments.

Patagonia’s once novel approach to sustainable materials, reducing emissions, prioritizing social good–and style of communicating about it all–is taught in sustainability grad programs everywhere. The company made fleece from plastic soda bottles, starting in 1993. It provocatively launched its ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ anti-consumption campaign on Black Friday in 2011. The company targets carbon neutrality by 2025 — and looks beyond that toward taking gross emissions to zero.

When sustainability professionals shrug, “We’re not Patagonia,” it’s not for lack of Patagonia trying to show them how to be. A new book (released in September), The Future of the Responsible Company: What We've Learned from Patagonia's First 50 Years, by Vincent Stanley with company founder Yvon Chouinard, builds (with 75 percent new content) upon their book The Responsible Company, published in 2012, which laid out their thesis around harm reduction, quality products and worker culture. The refresh, according to the book’s preface, is intended to account for the “dramatic shifts” that “have taken place in the world and at Patagonia” since the original version.

It expounds on what it means to be responsible to six audiences: owners/shareholders, workers, customers, community, nature and society, with candid examples from Patagonia’s own challenges getting it right.

With the book’s advice in mind, I spoke with author Vincent Stanley, director of Patagonia philosophy (that’s his real title), about what makes the company different, and why its methods seem so hard for other businesses to emulate. It comes down to three main themes.

“We are the same as every other business in 99% of our needs, our aspirations, our operations. There's not that much difference.”

Patagonia doesn’t make or sell low-quality products

It had a head start on this. “One of the things that helped direct our fate,” said Stanley, “was the fact that we came out of building climbing gear.” In that business, customers “are trusting their lives to the quality of what you're making.”

Patagonia’s predisposition for high quality, at least in part, led to a high price point. As a result, the company, which remains on the small size of big, with $1.5 billion in annual revenue, can afford to be sustainable: It has both the social license and the capital.

But it isn’t always easy. Stanley says that the company’s laser-focus on premium quality apparel “mostly came about in a negative way, in which we would discover something that we were doing, or was being done in the supply chain in our name, that we were ashamed of, and that we wanted to change.” Perfluorinated compounds (aka PFAS) are an example. Recently, after a phase-out process that took 15 years, the company announced it’s converting all of its “durable water-repellent membranes and finishes to non-fluorinated alternatives by 2025.”

All that R&D adds costs, and Patagonia’s customers will pay part of that to stay dry. So what if you don’t have that pricing wiggle room? “Being the lowest-cost provider really works against a lot of [what] needs to be done to improve performance,” he acknowledges, while giving due respect to McDonald’s and Walmart for their efforts to change the systems they work within in order to do better.

Patagonia sweats the small stuff and the big stuff

Toward the end of the book, The Future of the Responsible Company includes a long checklist of what I would deem “small stuff,” from mulching your landscaping to providing low-emission employee transportation options. Many sustainability professionals remain mired in pushing for things like this and never making it to the big, systemic changes — new business models, approaches to energy and water and alternatives to fossil fuels. For that reason, I tend to have little patience for these at-the-margins initiatives. Why does Patagonia spend time on them, and why recommend them to others?

“You have to look at material impacts,” he acknowledges. “For us, more than 90% of our impact is in the materials that we use. But it makes a difference to our approach to our material use to pay attention to every activity…it keeps you honest, in a way. It also keeps everybody engaged.” He pointed out that Patagonia’s trade show booths are reused for 10 years, and fully recycled at end of life.

Patagonia doesn’t make excuses

In chapter two, the new book reveals that “Patagonia was meant to be an easy-to-milk cash cow, not a risk-taking, environment-obsessed, navel-gazing company,” but that the founder and staff’s love for the outdoors – and protecting their favorite surf breaks and mountain passes – organically predisposed them to ask questions about environmental impact, like the many downsides of cotton. Their own life transitions — having kids — led to social innovations like onsite daycare. And their interest in transparency was inspired by employees’ curiosity and desire to explain what they were learning. All of these reinforced the company’s positive reputation among those who share its values.

I asked Stanley, “What do you say to those who respond to your recommendations with ‘Well, Patagonia is different. They get to do things differently, and we don't.’”

“There's always a good excuse for falling short,” he said. “I remember when [Patagonia was] very small, and people within the company, when we would be debating on what to do, they'd say, ‘Well, we're too small a company to do that.’ And then we got to a certain size, and in the same debates, I’d hear, ‘Oh, well, we're too big a company to do that.’ I would really discourage people from coming up with — or accepting — excuses. There are always things that we can't do. But it's not a good habit to get into to say, ‘Oh, well, you know, Patagonia is Patagonia, and they're a one-off.’ We are the same as every other business [in] 99% of our needs, our aspirations, our operations. There's not that much difference. So if we can do something— and we're still in business, and we're still profitable — I think people might pay attention to that.”

Source: Dylan Siegler, SVP, Sustainability at GreenBiz Group

As the world's nations enter another round of talks this week on creating a first-ever treaty to contain plastic pollution, officials are bracing for tough negotiations over whether to limit the amount of plastic being produced or just to focus on the management of waste.

Working with a document called a "zero draft" that lists possible policies and actions to consider, national delegates to the weeklong meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, will be debating which of those options to include in what eventually would become a legally binding treaty by the end of 2024, officials involved in the negotiations said.

"We are at a pivotal moment in this process," said David Azoulay, a managing attorney of the Center for International Environmental Law who is an observer to the negotiations.

The world is currently producing about 400 million tonnes of plastic waste every year, with less than 10% of it being recycled, according to the UN Environment Programme, choking landfills and despoiling oceans. That produced amount is set to surge in the coming decade, as oil companies, which often also produce plastics, look to new sources of revenue amid the energy transition away from fossil fuels.

Today, about 98% of single-use plastic - like bottles or packaging -is derived from fossil fuel, according to the U.N. Environment Programme.

The European Union and dozens of countries, including Japan, Canada and Kenya have called for -a strong treaty with "binding provisions" for reducing the production and use of virgin plastic polymers derived from petrochemicals and for eliminating or restricting problematic plastics, such as PVC and others containing toxic ingredients.

That position is opposed by the plastic industry and by oil and petrochemical exporters like Saudi Arabia, who want to see plastic use continue. They argue that the treaty should focus on recycling and reusing plastics, sometimes referred to in the talks as "circularity" in the plastics supply.

In a submission ahead of this week's negotiations, Saudi Arabia said the root cause of plastic pollution was "inefficient management of waste."

The United States, which initially wanted a treaty comprised of national plans to control plastics, has revised its stance in recent months. It now argues that, while the treaty should still be based on national plans, those plans should reflect globally agreed goals to reduce plastic pollution that are "meaningful and feasible," a U.S. State Department spokesperson said in a statement to Reuters.

The International Council of Chemical Associations wants the treaty to include measures "that accelerate a circular economy for plastics," according to council spokesperson Matthew Kastner.

"The plastics agreement should be focused on ending plastic pollution, not plastic production," Kastner told Reuters in a statement.

For oil, gas and petrochemical producers and exporters, a strong treaty is liability that could curb the sale of fossil fuels, said Bjorn Beeler, international coordinator of the International Pollutants Elimination Network.

Saudi Arabia and other producers are "pushing a 'bottom up' approach that makes individual countries responsible for the cleanup, health, and environmental costs of plastics and chemicals while leaving the fossil fuels and plastics industries off the hook," Beeler said.

Countries will also be debating whether the treaty should set transparency standards for chemical use in plastics production.

But before they can work on the substantive points, delegates will need to resolve procedural objections that slowed the talks in June when Saudi Arabia said decisions should be adopted by a majority of countries rather than by consensus. A consensus would allow one country to block the treaty's adoption. Most other countries did not support the intervention.

The Saudi delegation did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Environmental groups said they hoped this week's talks can focus on the treaty's substance, and move beyond the procedural discussions that stall progress.

"We need a radical rethink of the global plastics economy and cannot get bogged down by derailing tactics and false solutions," said Christina Dixon of the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Source: Reuters (Reporting by Valerie Volcovici; Editing by Katy Daigle and Aurora Ellis)

The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) and The World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) have announced a new partnership to establish a structured framework for hotel sustainability, leading to GSTC Certification.

The partnership endorses the existing WTTC Hotel Sustainability Basics while paving the way for a stepped progression toward GSTC Certification for sustainable hotels.

The three-stage framework for hotel sustainability will now see the integration between the WTTC Hotel Sustainability Basics verification and GSTC Certification, designed to support hotels in their pathway towards full sustainability.

Randy Durband, CEO of GSTC, said: “WTTC Hotel Sustainability Basics is a finely crafted entry level for hotels of any size and type to begin their journey to sustainable practices. GSTC’s certification by GSTC-Accredited Certification Bodies is recognised widely as the gold standard in certification of sustainable hotels, with the highest levels of assurance that exists.

“Today’s announcement of the combined pathway provides clarity for beginning and for continuous improvement. Stages must be just that, stages, and not levels to reach and stay in place.”

In an era where sustainability is paramount, GSTC and WTTC are joining forces to send a potent message to the market regarding the coherence and collaboration in the Travel and Tourism sector, said a statement.

Julia Simpson, WTTC President & CEO, said: “Collaborating with an esteemed body like GSTC reinforces our dedication to leading the industry towards a more sustainable future. It's imperative that we work with key global players like GSTC to drive change, set benchmarks, and inspire others to follow.

“With members spanning across the world, GSTC's rigorous accreditation program not only elevates our initiative but also ensures that the hospitality sector worldwide moves toward a unified vision of sustainability.”

The WTTC Hotel Sustainability Basics are already accessible to the industry, and the next phase in collaboration with GSTC is scheduled to launch in 2024.

This will provide the crucial stepping stone between WTTC Hotel Sustainability Basics, a three-year programme, and GSTC’s rigorous certification, ensuring a gradual yet comprehensive progression towards sustainability in hospitality, said a statement.

Source: Zawya

In recent years, climate change has risen to the top of the CEO agenda. A recent poll shows that Fortune 500 CEOs consider climate action a top priority, not only in its own right, but also for their business: It can enhance employee engagement, strengthen bonds with customers, and open up new markets. Almost every large company has launched initiatives to reduce carbon emissions, and many have announced net zero objectives. Yet climate change is only one part of a much broader challenge to protect our biosphere—the natural system in which humanity’s social and economic systems are embedded—and avert environmental collapse.

While combating climate change has been the focus in recent years, tackling biodiversity loss is emerging as an additional key priority for the next decade. Many governments and international bodies are increasingly concerned about this issue; in December 2022, 188 countries signed the Global Biodiversity Framework at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montréal. For businesses, this will mean dealing with growing pressures from consumers and regulators to act on biodiversity—in addition to the direct risks associated with deteriorating ecosystems.

Business leaders who want to mitigate the deleterious effects of biodiversity loss need to get their houses in order now. But compliance and defensive moves are only the start: In this period of upheaval and change, new winners will be determined by their ability to reimagine their business and find new sources of advantage.

In this article, we outline how companies can tackle the biodiversity challenge on a deeper, strategic level—protecting our ecosystems while positioning themselves for success.

Separating Myth from Fact in Biodiversity

To make the right strategic pivots, company leaders need a precise understanding of the nature and dynamics of the biodiversity challenge. We have identified four myths that often set companies on the wrong path.

Myth 1: Biodiversity is important only for the sake of nature.

Fact: Biodiversity is crucial to maintaining the ecosystem services upon which our economy, our society, and our lives depend.

Ecosystems provide a wide variety of essential services: They create the resources and raw materials that serve as inputs for our economic activities (provisioning services). They provide tranquility, serenity, and aesthetics to soothe our minds and vivify the human experience (cultural services). And they shape and sustain our physical environment by regulating the climate, preserving and regenerating soil, controlling floods, filtering pollutants, sequestering waste, pollinating crops, and much more (regulating and maintenance services). These services are the foundations of our modern societies and economies, as well as for life itself.

Biodiversity is the key factor that determines the health of ecosystems and their ability to provide these services. Preserving a variety of functional capabilities across the species of an ecosystem ensures that it can absorb shocks and adapt to changing circumstances. Significant deteriorations in biodiversity may result in a regime change of an ecosystem. For example, a rainforest may be transformed into a savannah due to the loss of keystone species; significant reduction in the number of seed dispersers, such as spider monkeys in the Amazon rainforest, would hamper plant reproduction; poaching of tigers in Malaysian rainforests may lead to an increase in herbivore populations, which could exert greater pressure on young tree saplings, inhibiting forest regeneration.

While the new ecosystem regime may be viable in its own right, the shift is still often harmful from a human perspective: Regime changes can make an ecosystem less productive for humans (e.g., eutrophication of lakes) and can necessitate challenging social adaptations (e.g., desertification in agricultural societies, aquatic depletion in fishing communities). Moreover, regime shifts at a local level may reduce the diversity of the global biosphere, undermining the complementary services different ecosystems provide—which are together essential for sustaining planetary equilibria (e.g., global deforestation harms the regulation of CO2 levels in the atmosphere). Finally, regime changes are typically self-reinforcing and hence difficult or highly expensive to reverse.

With the ongoing, rapid decline in biodiversity—studies show that extinctions of species are now occurring at between 100 to 1,000 times the pre-Anthropocene rate, and still accelerating[2]—there are serious concerns that a wide variety of ecosystems across the world will undergo regime shifts, losing their ability to provide services essential to not just nature, but also to humanity, society, and our economy.

Myth 2: By tackling climate change, we are already addressing biodiversity challenges.

Fact: While climate change is an important contributor to biodiversity loss, other unrelated factors are of similar significance. Moreover, some solutions to climate change are counterproductive for improving biodiversity. Hence, specific biodiversity solutions are required.

Climate change is an important cause of biodiversity loss—think of the bleaching of coral reefs. Moreover, biodiversity loss and climate change have a set of common causes, such as deforestation. However, there are also significant drivers of biodiversity loss that are unrelated to the climate problem. For example, the destruction or fragmentation of habitats, unsustainable harvesting practices (e.g., excessive logging or fishing), or pollution can all contribute to biodiversity loss.

Thus, solutions to climate change are only partially helpful for mitigating biodiversity loss, and indeed may prove harmful in many cases. For example, large-scale renewable energy projects, such as generating energy from wind, solar power, or biofuels, often require large areas of land; this can lead to deforestation, habitat destruction, or ecosystem fragmentation. The electrification of vehicles requires mining for rare metals at the expense of disrupting the local landscape. Hydroelectric dams restrict the movement of aquatic species, which obstructs migratory routes and alters the natural flow of rivers—which disrupts their ecological balance. Large-scale tree planting as a way to offset carbon emissions often creates monocultures and introduces non-native tree species, threatening local ecosystems and habitats.

There is an urgent need to move from a narrow focus on climate to a broader understanding of our embeddedness in natural systems, so that our actions can be evaluated with a full view of their consequences on the biosphere.

Myth 3: Biodiversity, like climate change, is exclusively a global problem.

Fact: While some aspects of the biodiversity challenge resemble the global collective action problem of climate change, other aspects are much more local in nature, producing entirely different dynamics and opportunities for action.

Climate change has global as well as local effects (e.g., desertification in Northern Africa). Its causes, while local and particular (e.g., carbon emissions from a specific factory), are pooled and mediated at the global level. There is no real link between the location of causes and global effects: reducing emissions in one country will not improve its climate in a commensurate way.

Meanwhile, many aspects of the biodiversity challenge are highly localized. For example, biochemical pollution and habitat destruction are typically caused by problems in the immediate area, which can be identified and addressed. This alters the dynamics of biodiversity loss in two significant ways. First, there is much greater scope for action to monitor, protect, or restore specific natural assets upon which your business depends. Second, there is much clearer accountability of actors who operate in and around a specific natural ecosystem.

Myth 4: To preserve biodiversity, businesses must simply reduce their own footprint.

Fact: Business impact on biodiversity is co-dependent with the behavior of other users and interacts with developments at larger spatial and temporal scales—which means companies need to follow a holistic and collaborative approach.

The harmful effects that companies have on the climate can be quantified and understood in a relatively straightforward manner by measuring their emissions of greenhouse gases. To be responsible on climate, a company needs to minimize these emissions.

Being responsible with respect to biodiversity is far more complicated. First, ecosystems are heterogeneous, meaning that the same species present in multiple ecosystems may play a vital role in some but a minor role in others. For example, cutting down a tree in one area could have vastly different consequences for the local ecosystem than cutting down the same species elsewhere because of different interactions with other parts of the system, such as funghi living in symbiotic relationships with the tree. Meanwhile, in terms of climate impact, cutting down a tree is equivalent to emitting around one ton of CO2, which is more or less equally harmful across the globe.

Second, the value of biodiversity is non-linear, meaning that the cost of cutting down trees within an ecosystem is not constant over time but may abruptly change as the tree population falls below certain critical thresholds. The consequence of heterogeneity and non-linearity is that ecologically responsible companies cannot just look narrowly to reduce their own footprint, but also need to look broadly to understand the status of and changes in the ecosystems they operate in (including the footprint of others with whom they share these ecosystems). This logic of the co-dependence of impacts underpins the need for local collaboration and governance systems that achieve responsible stewardship.

Third, ecosystems interact with one another at different spatial and temporal scales. While the health of ecosystems can to a large extent be analyzed in terms of local causes, there are also important interdependencies at the regional, national, and global level—for example, shifts in the pattern of the Gulf Stream. Collaboration at global levels is therefore also necessary to understand and address these large-scale, structural changes, as well as their effects on local ecosystems.

The Collective Agenda on Biodiversity Loss

While businesses should approach biodiversity loss strategically, by mitigating risks and seeking new opportunities, they should also situate their approach within a broader collective agenda. This collective agenda lays out the key transitions necessary to embed our socio-economic systems in our natural environment:

- Address knowledge gaps. Our understanding of the complexity and interconnectedness of ecosystems is far from complete. For example, it is estimated that less than 20% of species on our earth have been described and documented (according to a 2011 study, 84% of land and 91% of marine species were still unknown).[3] Additionally, we know that the dynamics of ecosystem change are non-linear, but we have a limited understanding of the specific tipping points—the threshold where regime change becomes self-reinforcing, and consequently, irreversible. This knowledge gap undermines our ability to assess risks and make informed decisions.To fill these knowledge gaps, more research is needed into the state and dynamics of ecosystems across the world, as well as their importance for, and sensitivity to, economic activity. Better data is the key unlock for such research. New data collection technologies, such as sensors and satellite images, need to be advanced and scaled rapidly. There is also a clear innovation and experimentation agenda for business, as they transition towards new materials, processes, and business models that allow for circularity and reduced impact.

- Modernize policies and institutions. Many legacy policies and institutional frameworks still incentivize behaviors that are detrimental for the biosphere, such as large-scale agricultural subsidies in the European Union or spatial planning policies that do not prevent the reduction or fragmentation of natural ecosystems. Furthermore, new policies are needed to curtail free-riding behaviors in markets, which suppress the motivation for businesses to lead the transition towards a more sustainable way of doing business. The need to curtail free riding is amplified at the global level—where much of the Global North is benefiting from ecosystem services produced in the Global South—which means there is also a need to modernize international policies, such that responsibilities and financial burdens are rebalanced for the maintenance of our global biosphere.

- Build effective governance models. The problem of biodiversity loss challenges our traditional models for collaboration and governance. We cannot rely on the market to finance and incentivize biodiversity-positive behaviors, such as investments in natural capital, because the value of ecosystem services is typically invisible and mobile – which means it is hard to measure, capture, attribute, and commercialize. Similarly, we cannot depend on traditional government regulations to stipulate in detail how we should take care of ecosystems, as ecosystems and our interactions with them are far too dynamic and heterogeneous for rigid regulation to be effective. The biosphere is an integral part of every aspect of our economy—the government can set boundaries, but it cannot control the actions of every major actor who operates within them.Instead, there is a need for new governance systems that simultaneously enable actors to overcome collective action problems while providing space for them to be responsive to changing ecosystem dynamics. One such emerging model obligates participants who rely on ecosystem services to compensate those managing the ecosystems that produce these services. This can operate at the global scale (e.g., international coalitions funding the Brazilian government for the preservation of the Amazon) or at the community level (e.g., tourists paying local inhabitants for the preservation of natural sites). Another governance model is “common pool resources,” wherein community members develop agreements on shared use and protection of the ecosystem, which is modelled on how older civilizations traditionally managed the “commons.” To advance the use of such governance models, it is necessary to combine a bottom-up approach of experimenting locally, synthesizing learnings, and scaling success stories, with a top-down approach of adapting institutional frameworks to enable them.

- Create universal reporting standards. Developing universal reporting standards is a critical component of the collective agenda, as it requires organizations to speak the same language. Consistent biodiversity reporting ensures that industries and sectors can collaborate on biodiversity efforts, avoiding a fragmented and inconsistent initiatives. It also allows organizations to develop shared understandings of biodiversity challenges, set targets, prioritize efforts, and track progress. Furthermore, universal reporting standards enable external parties to evaluate companies. This streamlines the regulatory process, simplifies due diligence processes for investors, and increases the transparency of a company’s practices.While there is a surge of new reporting frameworks and standards, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), much remains to be done. First, consensus has yet to emerge on standardization and interoperability of systems. Second, further innovation is necessary to build and deploy technologies that allow for more expansive and more precise data collection on the health and dynamics of ecosystems, enabling more accurate measurements and accounting. Third, there is a need to catalyze and accelerate adoption.

- Alleviate “sustainability scarcities.” It is key to create the conditions in different industries for a swift transition towards biodiversity-positive business. Action can be taken collectively—either by alliances of businesses or by public agencies—to overcome bottlenecks and clear roadblocks. For example, a lack of ecological expertise within industries can be alleviated by investments in education; a lack of access to essential raw materials for more sustainable technologies can be addressed with collective trade agreements or investment in developing alternatives. While individual companies can move early to avoid getting trapped in their transitions by such sustainability scarcities, there is also a clear collective agenda to eliminate these scarcities where feasible.

Defensive Moves: Protecting the Current Business Model

Having better understood the dynamics of the biodiversity challenge, how can businesses tackle the issue of biodiversity loss strategically? Below, we outline five types of defensive moves to protect the current business model.

Move early on compliance.

Biodiversity is emerging as a key priority on the regulatory agenda, as illustrated by the overwhelming support for the ambitious Global Biodiversity Framework developed at COP15. One of the framework’s targets charges governments with adopting legal requirements on monitoring and mitigation for large and transnational companies. This clause places businesses at the center of the conversation on biodiversity and is moving from a language of incentivization and voluntary action to a language of obligation and mandatory action. The ambitions of the framework are already starting to materialize in legislation, for example, with the development of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the Nature Restoration Law.

While compliance with regulation is necessary for every company, moving early offers opportunities for advantage. Compliance is likely to require new capabilities, such as taking stock of your dependencies on natural assets, determining your impact on natural ecosystems, and establishing processes to mitigate that impact. Anticipating upcoming regulation enables firms to attract talent, develop expertise, and experiment with solutions. For example, Tesla capitalized early on the tightening regulatory landscape for carbon emissions: Its action on the Zero Emissions Vehicle Credit and the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard gave the company a significant competitive edge.[4]

Collaborate externally to shape standards and regulations.

Beyond merely anticipating emerging standards and regulations, companies should take the opportunity to shape them by collaborating with other organizations, such as other companies, public agencies, and academic institutions. Doing so will provide several advantages:

Staying at the vanguard of change. As standards and regulation on biodiversity are still rapidly evolving, companies can only anticipate new standards and regulations in a timely manner by being part of the vanguard that drives them. The Science-Based Targets Network (SBTN), for example, is emerging as key framework for setting climate and nature-related targets and recently published its first list—with seventeen frontrunners, such as GSK, H&M Group, and Nestlé, seizing the opportunity to pilot its implementation.

Learning from others. Biodiversity standards and regulations often involve complicated methodologies. Hence businesses can benefit greatly from exchanging know-how and best practices with others. Organizations such as Business for Nature, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, and the Capitals Coalition facilitate knowledge-sharing and provide support to business leaders who want to experiment with new methods.

Better standards and regulations. The playbook on biodiversity is being developed as it is being deployed. To catalyze the realization of standards and regulations that protect the biosphere while creating opportunities for business, it is important to contribute to the development process. Communities like Business for Nature have played a leading role in shaping the Global Biodiversity Framework. In another example, IKEA and H&M, along with other corporations, worked closely with SBTN to shape methodologies for target-setting and action on biodiversity loss. SBTN was “road-tested” by more than 115 companies ahead of its May 2023 release.

Monitor the health of natural assets upon which your business depends.

Beyond complying with regulation on biodiversity-related impacts, companies should also evaluate the threat of ecosystem decline to their specific business.

The deterioration of natural assets upon which a business depends represents a significant risk. Many corporations around the world are already facing resource shortages due to the deterioration of provisioning services of ecosystems, such as forestry, fishing, and the cosmetics industry. Soil degradation is threatening the productivity of agriculture. Other companies are struggling with the breakdown of regulatory and maintenance services of nature, such as the ability of local ecosystems to absorb and break down industrial waste or restore biochemical balances in water, air, and soil.

To protect business continuity, monitoring biodiversity-related risks is imperative. This requires a four-step approach: First, analyze upon which natural assets your business is highly dependent. This step includes accounting for the use of resources across the supply chain and your reliance on maintaining and regulating the services of ecosystems. Second, inventory the state of the natural assets upon which you depend—both quantitatively and qualitatively—to estimate risks and identify the need for mitigative action. Third, track the state of these natural assets systematically over time. Fourth, anticipate future developments of these ecosystems to ensure you stay ahead of the curve.

Mitigate your negative impact on biodiversity.

Once firms have determined their dependency on natural assets and established systems to monitor those assets, executives can mitigate their depletion. Firms can use the data they collect on their natural resources to prioritize efforts and take targeted action. Mitigation can take many forms based on the industry, including the adoption of circular business models, which close the traditional take–make–waste process by using existing materials and products as inputs into their business model.

In the fashion industry, for example, H&M has piloted a variety of programs to experiment with a circular business model, including the resale of secondhand items and offering in-store repair services.[5] In the food industry, Danone has deployed a program aiming to source 100% of its ingredients in France from regenerative agriculture by 2025.[6]

Invest in the replenishment of natural capital.

Beyond protecting key natural assets upon which their business depends, companies can invest in replenishing them. Similar to investing in human capital—for example, through employee training—firms can invest strategically to increase their natural capital by supporting the ecosystems that they rely on. For example, IKEA has partnered with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to develop reforestation projects in nineteen locations, aiming to make Ikea’s operations biodiversity-positive—including the restoration of 18,500 hectares of rainforest in Borneo, Malaysia.[7]

Strategic Opportunities: Reimaging the Business Model

While defensive moves are necessary for protecting today’s business, they are the lowest form of adaptation. Tomorrow’s winners will embrace the opportunities for competitive advantage offered by the biodiversity challenge by reimagining their business models to overcome constraints and break trade-offs. By demonstrating precedents for positive benefit to business, they will also encourage other businesses to engage in protecting and building biodiversity.

Innovate to overcome new constraints.

Biodiversity is creating new constraints for businesses to grapple with, such as the rising scarcity of resources and regulatory limits on waste production. In response, companies can either compromise—for example on costs or the quality of their product—or they can innovate to overcome these constraints. While adopting existing approaches to monitoring and mitigating biodiversity-related risks is necessary, innovating to find new pathways towards an ecologically sustainable business creates new opportunities for differentiation and advantage.

One approach is resource substitution. Biohm, a biomanufacturing company, has developed sustainable building materials using the by-products, or “wastes,” of other industries.[8] In doing so, the company has developed an innovative solution to biodiversity constraints that positions them along the frontier of sustainability practices within their industry.

Monetize biodiversity-positive services.

Beyond targeted innovations to address their own biodiversity risks, companies can unlock new revenue streams by offering biodiversity solutions to others. Successful business practices that solve biodiversity challenges can be repackaged into products and services for other companies. GROW Oyster Reefs, for example, has designed a concrete mix that restores oyster ecosystems, which are essential to prevent the erosion and collapse of shorelines.[9] The company has deployed this successfully as part of infrastructure projects in England, the United States, and Mexico.

In building biodiversity-related services, a best practice is to leverage existing assets, technologies, and capabilities, thus creating new potential for synergies. Dow Chemical Company, for example, partnered with cosmetics brand Natura & Co to identify plant species on the former’s lands in the Amazon (where it operates charcoal and silicon plants) that are of commercial interest to the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries.[10] Through the sustainable extraction and sale of these plant species, Dow has unlocked a new revenue stream from its natural assets in the Amazon—which in turn incentivizes the company to preserve the biodiversity within this ecosystem.

Leverage nature as an innovation partner.

Biodiversity has always been a key source of innovation for humanity, from the discovery of penicillin to the creation of sonar technology (by emulating the echolocation of dolphins). Today, nature continues to inspire innovation in fields such as biomimetic robotics and the development of new drugs. But nature can be more than a passive resource to draw upon for our innovation efforts: We can actively work with nature as an innovation partner by leveraging the new potential of synthetic biology and artificial intelligence.

Embrace the magic of local.

Safeguarding the health of ecosystems requires that companies not only adjust their own processes, but also actively collaborate externally to ensure the responsible stewardship of natural assets. Essentially, our encroachment on the boundaries of local ecosystems forces local businesses to coordinate and cooperate more closely on responsibly using, preserving, and replenishing the ecosystems they collectively depend on. This is a modern version of the age-old problem of “managing the commons.”

The purpose of collaboration is to strive for a balanced portfolio of economic activity within the natural ecosystem, where different businesses are complementary and circular instead of compounding and exhaustive. Local business alliances can also pool resources and capabilities to achieve effective monitoring and mitigation. An example of a successful local alliance is found in California, where agriculture companies are joining forces to improve the sustainability of irrigation systems to address water shortages.

Pioneering companies can orchestrate local alliances on favorable terms and position themselves strategically. In Japan, the private sector is building local alliances to strengthen and commercialize satoyamas, rural landscapes supported by traditional knowledge, that conserve and enhance local biodiversity.[11] Kirin Holdings Company, for example, is working with communities to embed its vineyards within local natural and socio-economic systems, to protect the natural ecosystem and drive opportunities for deeper collaboration.

Orchestrating strong local alliances requires that a company gives its regional units sufficient agency to make decisions that work well under the local circumstances. This bottom-up approach can take the form of empowering managers of plants to collaborate with local partners and design their own roadmap towards effective monitoring and mitigation.[12] Solvay, a multinational chemical company, uses such an approach. Its headquarters subsequently synthesize local plans into a coherent roadmap, which allows the company to orchestrate knowledge-sharing among plants with similar challenges. Such a polycentric approach—with shared agency in decision-making across organizational layers—allows Solvay to connect global action with a deep understanding of the dynamics present in the communities most proximate to the local ecosystem, allowing for a more concerted, and ultimately more effective, approach to protecting biodiversity.

Put nature at the core of the customer experience.

Nature-based market opportunities don’t just exist behind the scenes; there is also a growing demand for nature as part of the customer experience. The breakdown of biodiversity is paired with the extinction of experience: the increasing degree to which citizens are removed and isolated from our natural surroundings, separated by layers of physical, social, and institutional barriers. The scarcity of the natural experience—and the growing awareness of the harmful side-effects for the human psyche—creates a business opportunity to incorporate elements of nature into products and services and their associated brand propositions.

Several nature-based enterprises are already growing fast; agritourism, for example, has rapidly grown into an USD 8 bn dollar market and is projected to sustain double-digit growth rates for the next decade.[13] Urban regeneration companies, which provide green infrastructure and building solutions to urban landscapes, are growing at a similar pace. Reintroducing nature in our everyday products and services is also necessary to create awareness about the presence and importance of our biosphere. As economist and biodiversity expert Sir Partha Dasgupta states, “if we care about our common future and the common future of our descendants, we should all in part be naturalists.” Companies can both support this transition of our collective consciousness, as well as use it as an opportunity to develop a differentiated offering.

With mounting pressure from regulators and scrutiny from consumers and investors, biodiversity loss is set to be the next arena in the battle for more sustainable business. Waiting for regulations to roll in and then merely striving for compliance is a recipe for being disrupted. Moreover, it means losing valuable time in the race to protect our planet. Instead, decision-makers need to move early to protect their business against risks from biodiversity loss, while also starting to imagine new business models for thriving amid new constraints.

Source: Martin Reeves and Jamaal Nimer, BCG Henderson Institute; Simon Levin, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University; Adam Job and Robert van der Veeken, Strategy Lab

Marking International Youth Day, the COP28 Presidency has joined hands with global online learning platform, Coursera, to provide 5,000 free licenses for a curated programme of climate-focused online courses and certificate programmes.

In line with COP28’s commitment to inclusion as the foundation of its presidency, the partnership will empower young people through education and capacity-building opportunities to meaningfully contribute to climate decision-making processes.

The programme of more than 100 courses covers a range of topics essential for climate literacy across mitigation, adaptation, finance, and loss and damage.

The distribution of these licenses will be facilitated through UNFCCC constituencies, the University Climate Network comprising 24 UAE-based universities and higher education institutions, and various youth activist groups.

Shamma Al Mazrui, COP28’s Youth Climate Champion, stated: “Young people have repeatedly raised that capacity building is a key priority for their meaningful participation during our global youth consultations. This partnership responds to that clearly identified need. COP28 and Coursera’s collaboration on climate education demonstrates our commitment to empower the younger generation and foster their active involvement in tackling the global climate crisis.”

Coursera: Partnering for progress

“Coursera is honored to partner with COP28 in the fight against climate change. Through education, we aim to empower thousands of young people to learn about climate issues and play a role in shaping sustainable solutions. This partnership reflects our commitment to making climate literacy accessible to all and nurturing a generation that will lead us toward a sustainable future,” said Jeff Maggioncalda, CEO of Coursera.

As part of the COP28 two-week thematic programme, December 8 is dedicated to ‘Youth, Children, Education and Skills’.

The day will spotlight the need to empower children and youth with clear, defined, and accessible opportunities to be a part of climate solutions proposed at every level.

Source: Gulf Business

According to a report issued by Honeywell, a majority of firms are planning greater expenditures in support of their sustainability objectives

Called the 3Q 2023 Environmental Sustainability Index, the report was published in collaboration with The Futurum Group. The paper added that firms worldwide are looking to spend more on sustainability objectives, despite economic uncertainties.

According to the fourth edition of the quarterly index, sustainability investment is expanding and will continue to rise, owing to the political and regulatory environment:

• 86% of the 751 global companies surveyed indicated that they plan to increase their sustainability budgets

• 7 in 10 surveyed companies said the political and regulatory environment has had a positive impact on their sustainability initiatives in the past 12 months

• 74% of respondents said they were optimistic about attaining sustainability goals, particularly with respect to 2030 energy goals – a strong number but 3 percentage points lower than the last index

• Budget increases are slated across four sustainability categories: energy evolution and efficiency, emissions reduction, pollution prevention, and circularity/recycling

• Improving energy evolution and efficiency is the top sustainability commitment across all geographies, with 87% of respondents citing it as a priority

• Some 25% and 20% of organisations in Latin America and Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), respectively, plan to boost their investment in energy evolution and efficiency by at least 50% in the coming 12 months – outpacing the budgetary commitments being made in North America and the Asia-Pacific

Sustainability has become a high focus for manufacturing and energy firms, with almost eight in ten organisations in both sectors selecting sustainability goals as their most significant effort for the next six months. Sustainability appears to be exceeding other company goals such as financial success, market expansion, and employee development in these organisations.

The most recent edition of the poll also discovered that sustainability reporting is robust, with 93% of survey organisations having a reporting procedure in place. 82% of these firms are confident that their reporting practices will fulfil future disclosure obligations. Managing the reporting process, on the other hand, is a bit more difficult, since just 38% claim they have a centralised person on staff to manage sustainability initiatives.

“The latest Environmental Sustainability Index confirms that large global companies are continuing to stay on pace and invest in technology and staff to achieve their environmental sustainability goals,” said Evan van Hook, chief sustainability officer at Honeywell.

“Middle East nations have been leading the way in the adoption and localisation of technologies to meet their climate targets, and in doing so are successfully transforming the ways that critical sectors of their economies operate,” said Mohammed Mohaisen, president and CEO, Honeywell Middle East and North Africa.

“The fourth release of Honeywell’s Environmental Sustainability Index provides new insight into how organisations are reporting and tracking their previously set commitments toward sustainability,” said Daniel Newman, principal analyst and founding partner of The Futurum Group. “This quarter, we are seeing increases in investment and transparency of efforts along with a balanced approach to technology versus process when it comes to reaching goals. As we move into 2024, we look forward to sharing data about our year-over-year comparison.”

Source: Technical Review Middle East

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has today issued its inaugural standards—IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 —ushering in a new era of sustainability-related disclosures in capital markets worldwide. The Standards will help to improve trust and confidence in company disclosures about sustainability to inform investment decisions.

And for the first time, the Standards create a common language for disclosing the effect of climate-related risks and opportunities on a company’s prospects.

The Standards will be officially launched by ISSB Chair Emmanuel Faber at the IFRS Foundation’s annual conference and through a week of events hosted by stock exchanges around the world, including those in Frankfurt, Johannesburg, Lagos, London, New York, Santiago de Chile; the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum is also hosting a launch event in Singapore.

About the Standards

IFRS S1 provides a set of disclosure requirements designed to enable companies to communicate to investors about the sustainability-related risks and opportunities they face over the short, medium and long term. IFRS S2sets out specific climate-related disclosures and is designed to be used with IFRS S1.

Both fully incorporate the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

A global baseline

The ISSB developed IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 with the benefit of extensive market feedback and in response to calls from the G20, the Financial Stability Board and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), as well as leaders in the business and investor community.

This support for a comprehensive global baseline of sustainability-related disclosures demonstrates the widespread demand for a consistent understanding of how sustainability factors affect companies’ prospects.

The ISSB Standards are designed to ensure that companies provide sustainability-related information alongside financial statements—in the same reporting package. The Standards have been developed to be used in conjunction with any accounting requirements. They are also built on the concepts that underpin the IFRS Accounting Standards, which are required by more than 140 jurisdictions. The ISSB Standards are suitable for application around the world, creating a truly global baseline.

Adoption of the ISSB Standards

Now that IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 are issued, the ISSB will work with jurisdictions and companies to support adoption. The first steps will be creating a Transition Implementation Group to support companies that apply the Standards and launching capacity-building initiatives to support effective implementation.

The ISSB will also continue to work with jurisdictions wishing to require incremental disclosures beyond the global baseline and with GRI to support efficient and effective reporting when the ISSB Standards are applied in combination with other reporting standards.

Emmanuel Faber, ISSB Chair, said:

Today represents the outcome of more than 18 months of intense work to deliver an inaugural set of sustainability disclosure standards for the global capital markets. The ISSB Standards have been designed to help companies tell their sustainability story in a robust, comparable and verifiable manner. We have consulted closely with the market to ensure the Standards are proportionate and will result in disclosures that are relevant for investment decision-making.

We know that better information leads to better economic decisions. Today’s publication is just the starting point as we consult on our future priorities, beyond climate.

Erkki Liikanen, Chair of the IFRS Foundation Trustees, said:

The global baseline approach, supported by the G20 and others, will provide investors with globally comparable sustainability-related disclosures that have the potential to move market prices, without constraining jurisdictions from requiring additional disclosures. This will help companies and investors by tackling duplicative reporting.

Takashi Nagaoka, Chair of the IFRS Foundation Monitoring Board, said:

The Monitoring Board welcomes the ISSB’s publication of IFRS S1 and IFRS S2. We will continue to collaborate closely with the leadership of the ISSB and the IFRS Foundation Trustees, and remain focused on supporting the ISSB’s ongoing and future work including on other sustainability topics beyond climate, to ensure continued robust governance, due process and oversight of the Foundation and its standard-setting boards.

Klaas Knot, Chair of the Financial Stability Board, said:

I welcome the publication today by the ISSB of its final standards on general sustainability-related disclosures and on climate-related disclosures. The publication of the ISSB standards marks an important milestone for achieving globally consistent disclosures.

Jean-Paul Servais, Chair of the International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSCO), said:

IOSCO has been actively involved in the IFRS Foundation’s consideration of whether and how to apply its trusted reputation and internationally renowned global standard-setting process to the topic of sustainability disclosures. We commend the leadership of the ISSB for the pace and quality of their work. IOSCO is conducting an independent assessment of the ISSB Standards, with a view to completing this review promptly.

Richard Manley and Carine Smith Ihenacho, Chair and Vice-Chair of the ISSB Investor Advisory Group, have welcomed the launch of IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 via a statement, commenting that:

High-quality data is necessary to support price discovery and capital formation, and facilitates efficient capital markets. ISSB Standards will equally support preparers in communicating sustainability information to their investors and other providers of capital.

Mary Schapiro, Head of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) Secretariat and Vice Chair for Global Public Policy at Bloomberg L.P., said:

"The global economy needs common reporting standards to reduce fragmentation and drive comparability in climate-related financial data. Built upon the foundation of the TCFD framework, the ISSB Standards provide a global baseline for companies to disclose decision-useful, climate-related financial information—information that is critical for creating more transparent markets, helping achieve a smooth low-carbon transition, and building a more resilient and sustainable global economy."

Ilham Kadri, Executive Committee Chair, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, said:

"I commend and applaud the ISSB for issuing both the climate-related and the general requirements disclosures standards: companies and investors are in dire need to have a common language to report and value their climate and social sustainability strategies."

Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman, World Economic Forum, said

"The publication of the first two ISSB Standards represents a vital step forward in establishing a global baseline for sustainability reporting. Consistent and comparable sustainability information, paired with financial information, empowers investors and stakeholders to gain a comprehensive understanding of a company’s performance and their commitment to driving sustainable value creation. We look forward to our continued collaboration."

Woochong Um, Managing Director General, Asian Development Bank, said:

"We welcome the inaugural IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards which deliver a global baseline of sustainability-related financial disclosures that have the potential to enhance Asian capital markets through attracting more investment and boosting private sector development in Asia. We encourage Asian Development Bank members to give their consideration to the adoption of the Standards."

Jean-François van Boxmeer, Chair, European Round Table for Industry (ERT) and Chair, Vodafone Group, said:

"ERT has strongly supported the ISSB and the development of a single trusted set of global standards for sustainability reporting. Global alignment is crucial to provide a comprehensive and clear view of a company’s sustainability performance and to allow for the comparability of disclosures on a global level. Separate and differing sets of standards for sustainability reporting in different jurisdictions would lead to a de facto double reporting for preparers and, consequently, unnecessary additional costs and reduced validity and comparability for users. We therefore strongly encourage jurisdictions around the globe, including the EU, to take on board the ISSB standards and to integrate them into their own regulatory framework."

Source: International Financial Reporting Standards

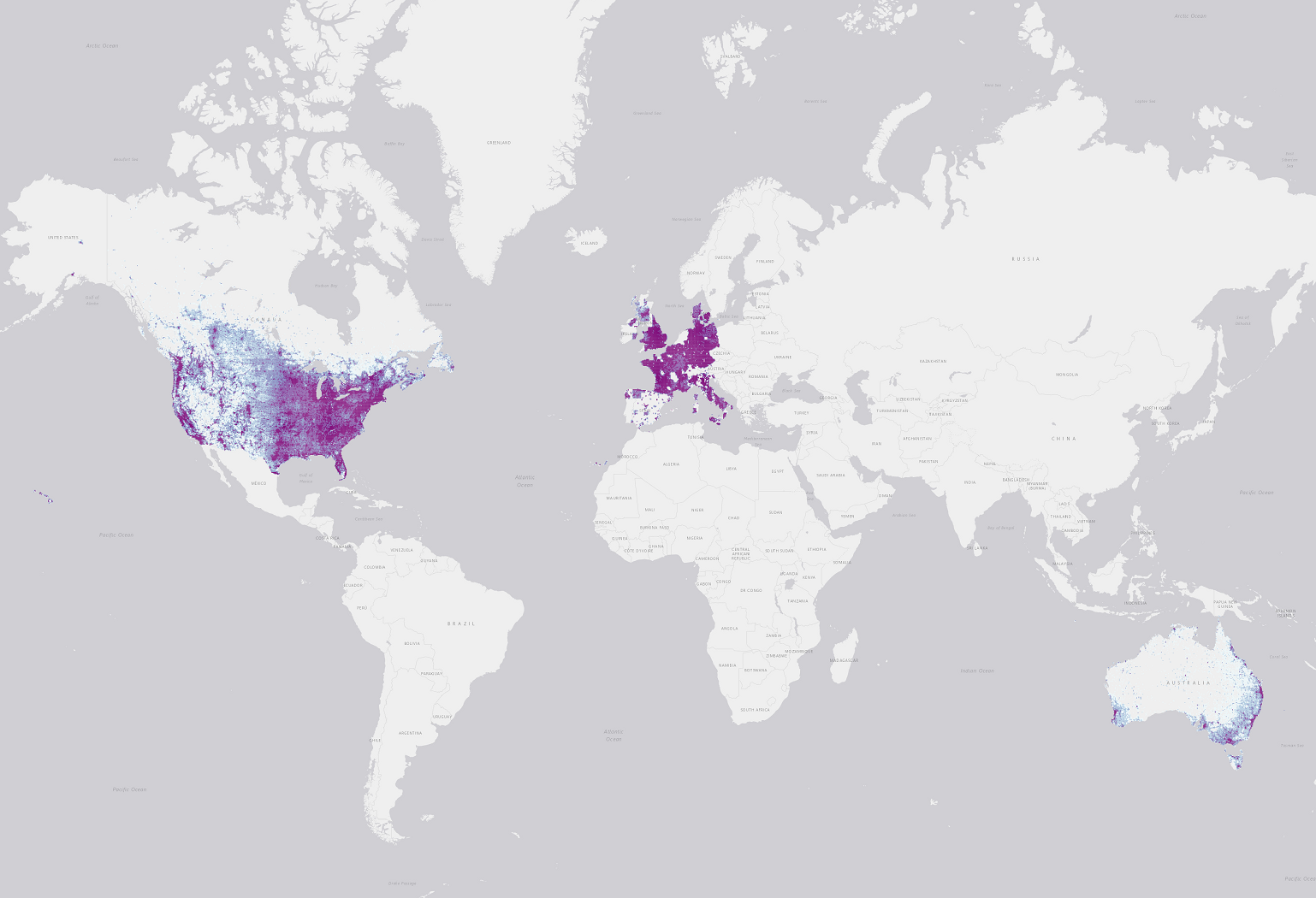

Microsoft Maps has a dedicated Maps AI (artificial intelligence) team that has been taking advantage of Microsoft’s investments in deep learning, computer vision, and ML (machine learning). Applying all that cool tech to mapping has yielded many useful datasets and our latest worldwide dataset includes a whopping 1.2B building footprints and 174M building height estimates from Bing Maps imagery between 2014 and 2023 including Maxar, Airbus, and IGN France imagery.

This release brings with it all the building footprint data from prior releases and includes the following regions:

Image Showing Global Building Footprints Coverage

Image Showing Global Building Footprints Coverage

...and brings a much-requested new dimension, building heights, for a subset:

Image Showing Global Building Footprints with Estimated Height Coverage

Image Showing Global Building Footprints with Estimated Height Coverage

You can find out all the great details and download it to use yourself from the open-source GitHub repository at GitHub - microsoft/GlobalMLBuildingFootprints: Worldwide building footprints derived from satellite imagery. If you want to see these building heights in action, check out the 3D view in the Windows Maps Application. You can also explore the dataset through Microsoft’s Planetary Computer: Microsoft Building Footprints | Planetary Computer.

Sample Showing Global Building Footprints over Bing Maps Imagery

Sample Showing Global Building Footprints over Bing Maps Imagery

Source: Microsoft Bing Blogs