Kohler Canada associates recognized a unique opportunity to use their water expertise to help solve the lack of access to clean, safe water for Canada’s Indigenous communities. To ensure meaningful impact, associates sought a partner that shared Kohler’s commitment to safe water for all and that was looking to implement sustainable, long-lasting solutions in communities across the country. Water First immediately stood out as a leader, not only bridging the clean water gap for Indigenous communities, but also providing access to training for water-treatment technicians.

Water First takes a holistic approach to providing access to clean water, and its programs are guided by the belief that people living in the community will have the clearest and deepest understanding of the challenges their community faces. Whether it’s poor infrastructure, contaminated source water, or something else entirely, needs will vary from community to community. And what sets Water First apart from other organizations is their focus on capacity building and training a new generation of technicians to operate and maintain water systems so the community can benefit for years to come.

As part of our partnership efforts, Kohler began directly supporting the Water First internship program, which trains Indigenous youth to become certified water-treatment plant operators. Now, over a year since Water First and Kohler teamed up, internship program graduates are applying their knowledge and skills to support the critical long-term sustainability of Indigenous communities’ drinking water systems.

This past October, eleven interns graduated from the program and are now working in local water- treatment plants to ensure safe water for their communities. One of the recent graduates is Hunter Edison, who currently works as his community’s only water operator in the Niisaachewan Anishinaabe Nation. In Hunter’s words, “Being an operator is quite the responsibility, not to be taken lightly. You’re not just keeping one person safe. Or just yourself. It’s the whole community. Before this, I didn’t realize that I could fulfill such an important role for my community.” Learn more about Hunter’s story here.

This “by the community for the community” approach is a core principle of Kohler’s partnership and innovation strategy for Kohler Safe Water for All. Water First’s commitment to training the next generation of Canada’s safe water keepers is one example of how communities and partners can collaborate to scale change. Partnerships like these pave the way for sharing expertise, experience, and resources to innovate and create a positive and lasting impact for the community and all of its members.

Source: csrwire.com

BARRIE – Eye doctors located in cities throughout Ontario are helping the planet and the local community by reducing waste and keeping otherwise non-recyclable disposable contact lenses and their packaging out of the landfill.

Through the Bausch + Lomb Every Contact Counts Recycling Program, consumers are invited to bring all brands of disposable contact lenses and their blister pack packaging to participating eye doctor locations to be recycled.

“Contact lenses are one of the forgotten waste streams that are often overlooked due to their size and how commonplace they are in today’s society,” said Tom Szaky, founder and CEO of TerraCycle. “Programs like the Bausch + Lomb Every Contact Counts Recycling Program allows eye doctors to work within their community and take an active role in preserving the environment, beyond what their local municipal recycling programs are able to provide. By creating this recycling initiative, our aim was to provide an opportunity where whole communities are able to collect waste alongside a national network of public drop-off locations all with the unified goal to increase the number of recycled contact lenses and their associated packaging, thereby reducing their impact on landfills.”

Source: TerraCycle

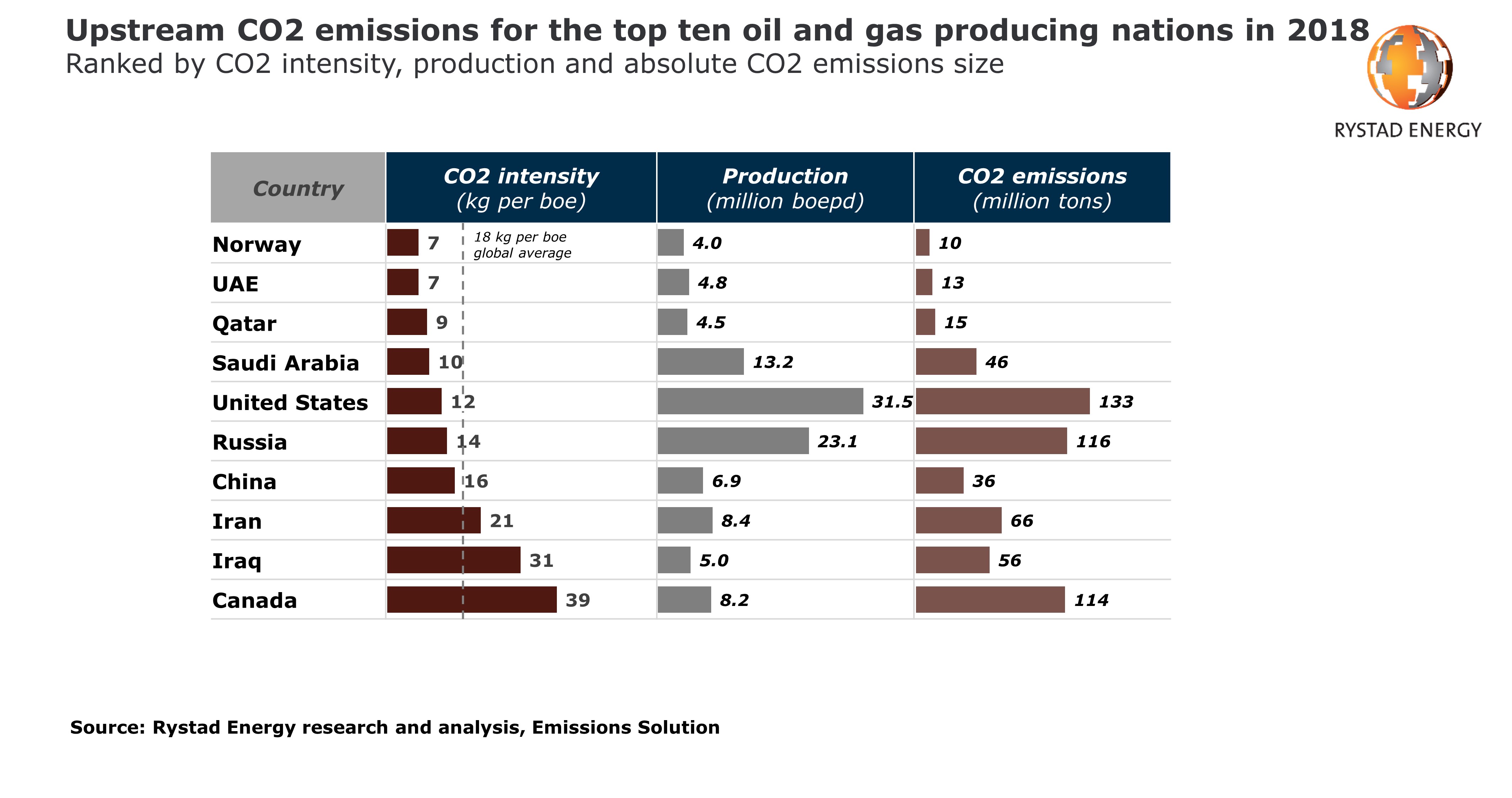

Rystad Energy has kickstarted its global emissions coverage, gathering key data and ranking the world’s oil and gas producers by how much CO2 is emitted in connection with their upstream activities. Our first such report, which will be published annually, shows that the US was the largest emitter in absolute terms in 2018*. Among the top 10 oil and gas producing countries, Canada had the highest CO2 emission intensity per barrel of oil equivalent (boe) produced, while Norway had the lowest.

For 2018, the year with the latest reliable data, the US was the world’s top emitter from upstream oil and gas producing activities in absolute terms, releasing a total of 133 million tons of CO2, followed by Russia (116 million tons) and Canada (114 million tons). The emission numbers referenced here do not include what we categorize as midstream elements (e.g. liquefaction plants).

Learn more in Rystad Energy’s Emissions Solution.

When it comes to CO2 intensity per produced boe, Norway shows the lowest upstream CO2 footprint among the top 10 producing countries, with approximately 7 kilos (kg) of CO2 per boe produced. Norway introduced a CO2 pricing mechanism in the early 1990s, while also adhering to the EU carbon trading system, which has motivated operators in the country to put extra emphasis on emission-reducing measures and technologies.

Several major Norwegian offshore fields, such as the giant Johan Sverdrup project, are now partly or fully electrified by power from shore, thus reducing CO2 extraction emissions substantially – even approaching zero in some instances. Furthermore, gas flaring has been banned in the country since the 1970s, with certain exceptions for safety purposes, which has resulted in a very low flaring intensity.

The UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are challenging Norway for the top position in terms of CO2 intensity, each with emissions at or below 10 kg per boe. Saudi Arabia and the UAE benefit from hosting large field developments with stable production levels and limited flaring, all of which contribute to low emission intensities. Moreover, production in these countries is dominated by light and medium grade crudes, which are less energy-intensive to extract compared to heavier oils.

At the other end of the scale, Canada and Iraq are both among the world’s highest upstream emitters, albeit for entirely different reasons.

Canada, with an average intensity of 39 kg per boe, has a high share of its production from oil sands, typically emitting three to five times more CO2 per barrel than the global average of 18 kg per boe. Heavy oil produced by mining or in-situ is more complicated to extract and the process is very energy-intensive. In recent years several major producers have divested their assets in these segments due to the expensive extraction process and the high carbon footprint.

Iraq, on the other hand, with an intensity of 31 kg per boe, has relatively low extraction emissions. However, the lack of gas infrastructure in the country means that significant volumes of associated gas are flared directly. The country must, in fact, import gas in order to meet its energy requirements. An expansion of Iraq’s domestic gas infrastructure would allow it to reduce flaring and imports, but such plans have yet to materialize.

“The average upstream CO2 emission intensity of oil and gas production worldwide was about 18 kg per boe in 2018, but the variation between producers is high – both in terms of countries and companies. Between individual fields, the variation is even higher,” says Rystad Energy’s Jon Erik Remme, Senior Upstream Analyst and Product Manager of Emissions Solution.

The amount of flaring served as a key distinguisher leading to a difference of 23 kg per boe observed between the highest and the lowest intensities in our analysis. In addition to flaring, the inherent differences in extraction emissions driven by the method of extraction, the field type, age of the field and other factors collectively yielded a difference of around 30 kg per boe between the highest and the lowest intensities.

*Note: Disclosure of emission data varies between countries, impacting the precision of emission estimates. Rystad Energy’s new global emissions report refers to numbers from 2018, given the wide discrepancy of country-level data quality for 2019. We will update our report with new 2019 projections at a later stage.